4.1. MAVRIC: Monaco with Automated Variance Reduction using Importance Calculations

D. E. Peplow and C. Celik

4.1.1. Introduction

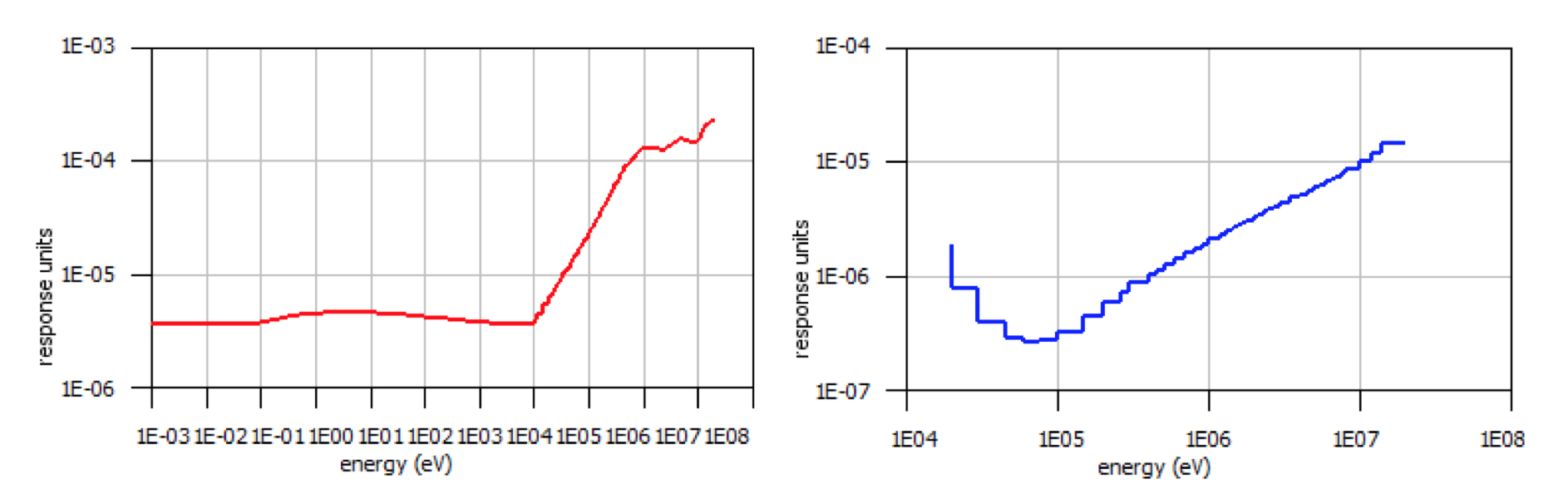

Monte Carlo particle transport calculations for deep penetration problems can require very long run times in order to achieve an acceptable level of statistical uncertainty in the final answers. Discrete-ordinates codes can be faster but have limitations relative to the discretization of space, energy, and direction. Monte Carlo calculations can be modified (biased) to produce results with the same variance in less time if an approximate answer or some other additional information is already known about the problem. If importances can be assigned to different particles based on how much they will contribute to the final answer, then more time can be spent on important particles, with less time devoted to unimportant particles. One of the best ways to bias a Monte Carlo code for a particular tally is to form an importance map from the adjoint flux based on that tally. Unfortunately, determining the exact adjoint flux could be just as difficult as computing the original problem itself. However, an approximate adjoint can still be very useful in biasing the Monte Carlo solution [MAVRIC-Wag97]. Discrete ordinates can be used to quickly compute that approximate adjoint. Together, Monte Carlo and discrete ordinates can be used to find solutions to thick shielding problems in reasonable times.

The MAVRIC (Monaco with Automated Variance Reduction using Importance Calculations) sequence is based on the CADIS (Consistent Adjoint Driven Importance Sampling) and FW-CADIS (Forward-Weighted CADIS) methodologies [MAVRIC-HW03, MAVRIC-Wag02, MAVRIC-WBP07, MAVRIC-WH98, MAVRIC-WPE20]. MAVRIC automatically performs a three-dimensional, discrete-ordinates calculation using Denovo to compute the adjoint flux as a function of position and energy. This adjoint flux information is then used to construct an importance map (i.e., target weights for weight windows) and a biased source distribution that work together-particles are born with a weight matching the target weight of the cell into which they are born. The fixed-source Monte Carlo radiation transport Monaco [MAVRIC-Pep11] then uses the importance map for biasing during particle transport, and it uses the biased source distribution as its source. During transport, the particle weight is compared with the importance map after each particle interaction and whenever a particle crosses into a new importance cell in the map.

For problems that do not require variance reduction to complete in a reasonable time, execution of MAVRIC without the importance map calculation provides an easy way to run Monaco. For problems that do require variance reduction to complete in a reasonable time, MAVRIC removes the burden of setting weight windows from the user and performs it automatically with a minimal amount of additional input. Note that the MAVRIC sequence can be used with the final Monaco calculation as either a multigroup (MG) or a continuous-energy (CE) calculation.

Monaco has a wide variety of tally options: it can calculate fluxes (by group) at a point in space, over any geometrical region, or for a user-defined, three-dimensional, rectangular grid. These tallies can also integrate the fluxes with either standard response functions from the cross section library or user-defined response functions. All of these tallies are available in the MAVRIC sequence.

Although it was originally designed for CADIS, the MAVRIC sequence is also capable of creating importance maps using both forward and adjoint deterministic estimates. The FW-CADIS method [MAVRIC-WPM14] can be used for optimizing several tallies at once, a mesh tally over a large region, or a mesh tally over the entire problem. Several other methods for producing importance maps are also available in MAVRIC and are explored in Sect. 4.4.

4.1.2. CADIS Methodology

MAVRIC is an implementation of CADIS (Consistent Adjoint Driven Importance Sampling) using the Denovo SN and Monaco Monte Carlo functional modules. Source biasing and a mesh-based importance map, overlaying the physical geometry, are the basic methods of variance reduction. To make the best use of an importance map, the map must be made consistent with the source biasing. If the source biasing is inconsistent with the weight windows that will be used during the transport process, then source particles will undergo Russian roulette or splitting immediately, wasting computational time and negating the intent of the biasing.

4.1.2.1. Overview of CADIS

CADIS is well described in the literature, so only a brief overview is given here. Consider a class source-detector problem described by a unit source with emission probability distribution function \(q\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) and a detector response function \(\sigma_{d}\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)\). To determine the total detector response, R, the forward scalar flux \(\phi\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) must be known. The response is found by integrating the product of the detector response function and the flux over the detector volume \(V_{d}\):

Alternatively, if the adjoint scalar flux, \(\phi^{+}\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), is known from the corresponding adjoint problem with adjoint source \(q^{+}\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right) = \sigma_{d}\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), then the total detector response could be found by integrating the product of the forward source and the adjoint flux over the source volume, \(V_{s}\):

Unfortunately, the exact adjoint flux may be just as difficult to determine as the forward flux, but an approximation of the adjoint flux can still be used to form an importance map and a biased source distribution for use in the forward Monte Carlo calculation.

Wagner [MAVRIC-Wag97] showed that if an estimate of the adjoint scalar flux for the corresponding adjoint problem can be found, then an estimate of the response R can be made using Eq. (4.1.2). The adjoint source for the adjoint problem is typically separable and corresponds to the detector response and spatial area of the tally to be optimized: \(q^{+}\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right) = \sigma_{d}\left(E \right)g\left( \overrightarrow{r} \right)\), where \(\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\) is a flux-to-dose conversion factor and \(g\left( \overrightarrow{r} \right)\) is 1 in the tally volume and is 0 otherwise. Then, from the adjoint flux \(\phi^{+}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) and response estimate R, a biased source distribution, \(\widehat{q}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), for source sampling of the form

and weight window target values, \(\overline{w}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), for particle transport of the form

can be constructed, which minimizes the variance in the forward Monte Carlo calculation of R.

When a particle is sampled from the biased source distribution \(\widehat{q}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), to preserve a fair game, its initial weight is set to

which exactly matches the target weight for that particle’s position and energy. This is the “consistent” part of CADIS-source particles are born with a weight matching the weight window of the region/energy into which they are born. The source biasing and the weight windows work together.

CADIS has been applied to many problems-including reactor ex-core detectors, well-logging instruments, cask shielding studies, and independent spent fuel storage facility models-and has demonstrated very significant speed-ups in calculation time compared to analog simulations.

4.1.2.2. Multiple sources with CADIS

For a typical Monte Carlo calculation with multiple sources—each with a probability distribution function \(q_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) and a strength \(S_{i}\), giving a total source strength of \(S = \sum_{}^{}S_{i}\)—the source is sampled in two steps. First, the specific source i is sampled with probability \(p\left( i \right) = \ S_{i}/S\), and then the particle is sampled from the specific source distribution \(q_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\).

The source sampling can be biased at both levels: from which source to sample and how to sample each source. For example, the specific source can be sampled using some arbitrary distribution, \(\widehat{p}\left( i \right)\), and then the individual sources can be sampled using distributions \({\widehat{q}}_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\). Particles would then have a birth weight of

For CADIS, a biased multiple source needs to be developed so that the birth weights of sampled particles still match the target weights of the importance map. For a problem with multiple sources—each with a distribution \(q_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) and a strength \(S_{i}\)—the goal of the Monte Carlo calculation is to compute some response \(R\) for a response function \(\sigma_{d}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) at a given detector,

Note that the flux \(\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) has contributions from each source. The response, \(R_{i}\), from each specific source (\(S_{i}\) with \(q_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\)) can be expressed using just the flux from that source, \(\phi_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), as

The total response is then found as \(R = \sum_{i}^{}R_{i}\).

For the adjoint problem, using the adjoint source of \(q^{+}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right) = \sigma_{d}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), the response \(R\) can also be calculated as

with the response contribution from each specific source being

The target weights \(\overline{w}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) of the importance map are found using

Each biased source \({\widehat{q}}_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) pdf is found using

and the biased distribution used to select an individual source is \(\widehat{p}\left( i \right) = \ R_{i}/\sum_{}^{}{R_{i} = R_{i}/R}\).

When using the biased distribution used to select an individual source, \(\widehat{p}\left( i \right)\), and the biased source distribution, \({\widehat{q}}_{i}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), the birth weight of the sampled particle will be

which matches the target weight, \(\overline{w}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\).

4.1.2.3. Multiple tallies with CADIS

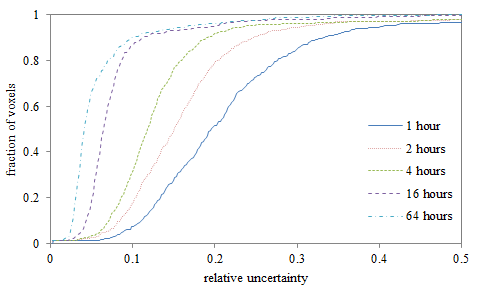

The CADIS methodology works quite well for classic source/detector problems. The statistical uncertainty of the tally that serves as the adjoint source is greatly reduced since the Monte Carlo transport is optimized to spend more simulation time on those particles that contribute to the tally, at the expense of tracking particles in other parts of phase space. However, more recently, Monte Carlo has been applied to problems in which multiple tallies need to all be found with low statistical uncertainties. The extension of this idea is the mesh tally-where each voxel is a tally for which the user desires low statistical uncertainties. For these problems, the user must accept a total simulation time that is controlled by the tally with the slowest convergence and simulation results where the tallies have a wide range of relative uncertainties.

The obvious way around this problem is to create a separate problem for each tally and use CADIS to optimize each. Each simulation can then be run until the tally reaches the level of acceptable uncertainty. For more than a few tallies, this approach becomes complicated and time-consuming for the user. For large mesh tallies, this approach is not reasonable.

Another approach to treat several tallies, if they are in close proximity to each other, or a mesh tally covering a small portion of the physical problem, is to use the CADIS methodology with the adjoint source near the middle of the tallies to be optimized. Since particles in the forward Monte Carlo simulation are optimized to reach the location of the adjoint source, all the tallies surrounding that adjoint source should converge quickly. This approach requires the difficult question of “how close.” If the tallies are too far apart, then certain energies or regions that are needed for one tally may be of low importance for getting particles to the central adjoint source. This may under-predict the flux or dose at the tally sites far from the adjoint source.

MAVRIC has the capability to have multiple adjoint sources with this problem in mind. For several tallies that are far from each other, multiple adjoint sources could be used. In the forward Monte Carlo, particles would be drawn to one of those adjoint sources. The difficulty with this approach is that typically the tally that is closest to the true physical source converges faster than the other tallies—showing that the closest adjoint source seems to attract more particles than the others. Assigning more strength to the adjoint source further from the true physical source helps to address this issue, but finding the correct strengths so that all of the tallies converge to the same relative uncertainty in one simulation is an iterative process for the user.

4.1.2.4. Forward-weighted CADIS

To converge several tallies to the same relative uncertainty in one simulation, the adjoint source corresponding to each of those tallies must be weighted inversely by the expected tally value. To calculate the dose rate at two points—say one near a reactor and one far from a reactor—in one simulation, then the total adjoint source used to develop the weight windows and biased source must have two parts. The adjoint source far from the reactor must have more strength than the adjoint source near the reactor by a factor equal to the ratio of the expected near dose rate to the expected far dose rate.

This concept can be extended to mesh tallies, as well. Instead of using a uniform adjoint source strength over the entire mesh tally volume, each voxel of the adjoint source should be weighted inversely by the expected forward tally value for that voxel. Areas of low flux or low dose rate would have more adjoint source strength than areas of high flux or high dose rate.

An estimate of the expected tally results can be found by using a quick discrete-ordinates calculation. This leads to an extension of the CADIS method: forward-weighted CADIS (FW-CADIS). First, a forward SN calculation is performed to estimate the expected tally results. A total adjoint source is constructed so that the adjoint source corresponding to each tally is weighted inversely by those forward tally estimates. Then the standard CADIS approach is used-an importance map (target weight windows) and a biased source are made using the adjoint flux computed from the adjoint SN calculation.

For example, if the goal is to calculate a detector response function \(\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\) (such as dose rate using flux-to-dose-rate conversion factors) over a volume (defined by \(g\left( \overrightarrow{r} \right)\)) corresponding to mesh tally, then instead of simply using \(q^{+}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right) = \sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\ g(\overrightarrow{r})\), the adjoint source would be

where \(\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) is an estimate of the forward flux, and the energy integral is over the voxel at \(\overrightarrow{r}\). The adjoint source is nonzero only where the mesh tally is defined (\(g\left( \overrightarrow{r} \right)\)), and its strength is inversely proportional to the forward estimate of dose rate.

The relative uncertainty of a tally is controlled by two components: (1) the number of tracks contributing to the tally and (2) the shape of the distribution of scores contributing to that tally. In the Monte Carlo game, the number of simulated particles, \(m\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), can be related to the true physical particle density, \(n\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right),\) by the average Monte Carlo weight of scoring particles, \(\overline{w}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), by

In a typical Monte Carlo calculation, tallies are made by adding some score, multiplied by the current particle weight, to an accumulator. To calculate a similar quantity related to the Monte Carlo particle density would be very close to calculating any other quantity but without including the particle weight. The goal of FW-CADIS is to make the Monte Carlo particle density, \(m\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), uniform over the tally areas, so an importance map must be developed that represents the importance of achieving uniform Monte Carlo particle density. By attempting to keep the Monte Carlo particle density more uniform, more uniform relative errors for the tallies should be realized.

Two options for forward weighting are possible. For tallies over some area where the entire group-wise flux is needed with low relative uncertainties, the adjoint source should be weighted inversely by the forward flux, \(\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\). The other option, for a tally in which only an energy-integrated quantity is desired, is to weight the adjoint inversely by that energy-integrated quantity,\(\int_{}^{}{\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\text{\ dE}\). For a tally in which the total flux is desired, then the response in the adjoint source is simply \(\sigma_{d}\left( E \right) = 1\).

To optimize the forward Monte Carlo simulation for the calculation of some quantity at multiple tally locations or across a mesh tally, the adjoint source must be weighted by the estimate of that quantity. For a tally defined by its spatial location \(g\left( \overrightarrow{r} \right)\) and its optional response \(\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\), the standard adjoint source would be \(q^{+}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right) = \sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\text{g}\left( \overrightarrow{r} \right)\). The forward-weighted adjoint source, \(q^{+}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\), depending on what quantity is to be optimized, is listed below.

For the calculation of |

Adjoint source |

|

|---|---|---|

Energy and spatially dependent flux |

\(\phi\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) |

\(\frac{g\left( \overrightarrow{r}\right)}{\phi\left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\) |

Spatially dependent total flux |

\(\int_{}^{}{\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\textit{dE}\) |

\(\frac{g\left( \overrightarrow{r}\right)}{\int_{}^{}{\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\textit{dE}}\) |

Spatially dependent total response |

\(\int_{}^{}{\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\phi \left(\overrightarrow{r},E\right)}\textit{dE}\) |

\(\frac{\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\text{g}\left( \overrightarrow{r} \right)}{\int_{}^{}{\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\phi \left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\textit{dE}}\) |

The bottom line of FW-CADIS is that in order to calculate a quantity at multiple tally locations (or across a mesh tally) with more uniform relative uncertainties, an adjoint source must be developed for an objective function that keeps some non-physical quantity-related to the Monte Carlo particle density and similar in form to the desired quantity-constant. FW-CADIS uses the solution of a forward discrete-ordinates calculation to properly weight the adjoint source. After that, the standard CADIS approach is used.

4.1.2.5. MAVRIC Implementation of CADIS

With MAVRIC, as with other shielding codes, the user defines the problem as a set of physical models-the material compositions, the geometry, the source, and the detectors (locations and response functions)-as well as some mathematical parameters on how to solve the problem (number of histories, etc.). For the variance reduction portion of MAVRIC, the only additional inputs required are (1) the mesh planes to use in the discrete-ordinates calculation(s) and (2) the adjoint source description—basically the location and the response of each tally to optimize in the forward Monte Carlo calculation. MAVRIC uses this information to construct a Denovo adjoint problem. (The adjoint source is weighted by a Denovo forward flux or response estimate for FW-CADIS applications.) MAVRIC then uses the CADIS methodology: it combines the adjoint flux from the Denovo calculation with the source description and creates the importance map (weight window targets) and the mesh-based biased source. Monaco is then run using the CADIS biased source distribution and the weight window targets.

4.1.2.5.1. Denovo

Denovo is a parallel three-dimensional SN code that is used to generate adjoint (and, for FW-CADIS, forward) scalar fluxes for the CADIS methods in MAVRIC. For use in MAVRIC/CADIS, it is highly desirable that the SN code be fast, positive, and robust. The phase-space shape of the forward and adjoint fluxes, as opposed to a highly accurate solution, is the most important quality for Monte Carlo weight-window generation. Accordingly, Denovo provides a step-characteristics spatial differencing option that produces positive scalar fluxes as long as the source (volume plus in-scatter) is positive. Denovo uses an orthogonal, nonuniform mesh that is ideal for CADIS applications because of the speed and robustness of calculations on this mesh type.

Denovo uses the highly robust GMRES (Generalized Minimum Residual) Krylov method to solve the SN equations in each group. GMRES has been shown to be more robust and efficient than traditional source (fixed-point) iteration. The in-group discrete SN equations are defined as

where L is the differential transport operator, M is the moment-to-discrete operator, S is the matrix of scattering cross section moments, q is the external and in-scatter source, \(\phi\) is the vector of angular flux moments, and \(\psi\) is the vector of angular fluxes at discrete angles. Applying the operator D, where \(\phi = \mathbf{D}\psi\), and rearranging terms, casts the in-group equations in the form of a traditional linear system, \(\mathbf{A}x = b\),

(4.1.17)\[\left( \mathbf{I} - \mathbf{D}\mathbf{L}^{- 1}\mathbf{\text{MS}} \right) = \mathbf{D}\mathbf{L}^{- 1}q .\]

The operation \(\mathbf{L}^{- 1}\nu\), where \(\nu\) is an iteration vector, is performed using a traditional wave-front solve (transport sweep). The parallel implementation of the Denovo wave-front solver uses the well-known Koch-Baker-Alcouffe (KBA) algorithm, which is a two-dimensional block-spatial decomposition of a three-dimensional orthogonal mesh [MAVRIC-BK98]. The Trilinos package is used for the GMRES implementation [MAVRIC-WH03] Denovo stores the mesh-based scalar fluxes in a double precision binary file (*.dff) called a Denovo flux file. Past versions of SCALE/Denovo used the TORT [MAVRIC-RS97] *.varscl file format (DOORS package [MAVRIC-RC98]), but this was limited to single precision. Since the rest of the MAVRIC sequence has not yet been parallelized, Denovo is currently used only in serial mode within MAVRIC.

4.1.2.5.2. Monaco

The forward Monte Carlo transport is performed using Monaco, a fixed-source shielding code that uses the SCALE General Geometry Package (SGGP, the same as used by the criticality code KENO-VI) and the standard SCALE material information processor. Monaco can use either MG or CE cross section libraries. Monaco was originally based on the MORSE Monte Carlo code but has been extensively modified to modernize the coding, incorporate more flexibility in terms of sources/tallies, and read a user-friendly block/keyword style input.

Much of the input to MAVRIC is the same as Monaco. More details can be found in the Monaco chapter of the SCALE manual (Sect. 8.2).

4.1.2.5.3. Running MAVRIC

The objective of a SCALE sequence is to execute several codes, passing the output from one to the input of the next, in order to perform some analysis—tasks that users typically had to do in the past. MAVRIC does this for difficult shielding problems by running approximate discrete-ordinates calculations, constructing an importance map and biased source for one or more tallies that the user wants to optimize in the Monte Carlo calculation, and then using those in a forward Monaco Monte Carlo calculation. MAVRIC also prepares the forward and adjoint cross sections when needed. The steps of a MAVRIC sequence are listed in Table 4.1.1. The user can instruct MAVRIC to run this whole sequence of steps or just some subset of the steps to verify the intermediate steps or to reuse previously calculated quantities in a new analyses.

The MAVRIC sequence can be stopped after key points by using the “parm= parameter ” operator on the “=mavric” command line, which is the first line of the input file. The various parameters are listed in Table Table 4.1.2. These parameters allow the user to perform checks and make changes to the importance map calculation before the actual Monte Carlo calculation in Monaco.

MAVRIC also allows the sequence to start at several different points. If an importance map and biased source have already been computed, they can then be used directly. If the adjoint scalar fluxes are known, they can quickly be used to create the importance map and biased source and then begin the forward Monte Carlo calculation. All of the different combinations of starting MAVRIC with some previously calculated quantities are listed in the following section detailing the input options.

When using MG cross section libraries that do not have flux-to-dose-rate conversion factors, use “parm=nodose” to prevent the cross section processing codes from trying to move these values into the working library.

MAVRIC creates many files that use the base problem name from the output file. For an output file called “c:path1path2\outputName.out” or “/home/path1/path2/ outputName.inp”, spaces in the output name will cause trouble and should not be used.

Cross section calculation |

XSProc is used to calculate the forward cross sections for Monaco |

Forward Denovo (optional) |

|

Cross section calculation |

XSProc is used to calculate the forward cross sections for Denovo |

Forward flux calculation |

Denovo calculates the estimate of the forward flux |

Adjoint Denovo (optional) |

|

Cross section calculation |

XSProc is used to calculate the adjoint cross sections for Denovo |

Adjoint flux calculation |

Denovo calculates the estimate of the adjoint flux |

CADIS (optional) |

The scalar flux file from Denovo is then used to create the biased source distribution and transport weight windows |

Monte Carlo calculation |

Monaco uses the biased source distribution and transport weight windows to calculate the various tallies |

Parameter |

MAVRIC will stop after |

|---|---|

check |

input checking |

forinp |

Forward Denovo input construction (makes |

forward |

The forward Denovo calculation |

adjinp |

Adjoint Denovo input construction (makes |

adjoint |

The adjoint Denovo calculation |

impmap |

Calculation of importance map and biased source |

4.1.3. MAVRIC input

The input file for MAVRIC consists of three lines of text (“=mavric” command line with optional parameters, the problem title, and SCALE cross section library name) and then several blocks, with each block starting with “read xxxx” and ending with “end xxxx”. There are three required blocks and nine optional blocks. Material and geometry blocks must be listed first and in the specified order. Other blocks may be listed in any order.

Blocks (must be in this order):

Composition – (required) SCALE standard composition, list of materials used in the problem

Celldata – SCALE resonance self-shielding

Geometry – (required) SCALE general geometry description

Array – optional addition to the above geometry description

Volume – optional calculation or listing of region volumes

Plot – create 2D slices of the SGGP geometry

Other Blocks (in any order, following the blocks listed above):

Definitions – defines locations, response functions, and grid geometries used by other blocks

Sources – (required) description of the particle source spatial, energy, and directional distributions

Tallies – description of what to calculate: point detector tallies, region tallies, or mesh tallies

Parameters – how to perform the simulation (random number seed, how many histories, etc.)

Biasing – data for reducing the variance of the simulation

ImportanceMap – instructions for creating an importance map based on a discrete-ordinates calculation

The material blocks (Composition and Celldata) and the physical model blocks (Geometry, Array, Volume, and Plot) follow the standard SCALE format. See the other SCALE references as noted in the following sections for details. The Biasing block and ImportanceMap block cannot both be used.

For the other six blocks, scalar variables are set by “keyword=value”, fixed-length arrays are set with “keyword value1 … valueN”, variable-length arrays are set with “keyword value1 … valueN end”, and some text and filenames are read in as quoted strings. Single keywords to set options are also used in some instances. The indention, comment lines, and upper/lowercase shown in this document are not required- they are used in the examples only for clarity. Except for strings in quotes (like filenames), SCALE is case insensitive.

After all input blocks are listed, a single line with “end data” should be listed. A final “end” should also be listed, to signify the end of all MAVRIC input. Nine of the blocks are the same input blocks as those used by the functional module Monaco, with a few extra keywords only for use with MAVRIC. These extra keywords are highlighted here, but without relisting all of the standard Monaco keywords for those blocks. See Example 4.1.1 for an overview of MAVRIC input file structure.

4.1.3.1. Composition block

Material information input follows the standard SCALE format for material input. Basic materials known to the SCALE library may be used as well as completely user-defined materials (using isotopes with known cross sections). Input instructions are located in the XSProc chapter (Sect. 7.1) in the SCALE manual. The Standard Composition Library chapter (Sect. 7.2) lists the different cross section libraries and the names of standard materials. An example is as follows:

read composition

uo2 1 0.2 293.0 92234 0.0055 92235 3.5 92238 96.4945 end

orconcrete 2 1.0 293.0 end

ss304 3 1.0 293.0 end

end composition

Details on the cell data block are also included in the XSProc chapter (Sect. 7.1). When using different libraries for the importance map production (listed at the top of the input) and the final Monte Carlo calculation (listed in the parameters block, if different), make sure that the materials are present in both libraries.

=mavric % name of sequence

Some title for this problem % title

v7-27n19g % cross section library name

read composition % SCALE material compositions

... % [required block]

end composition %

read celldata % SCALE resonance self-shielding

... % [optional block]

end celldata %

read geometry % SCALE SGGP geometry

... % [required block]

end geometry %

read array % SCALE SGGP arrays

... % [optional block]

end array %

read volume % SCALE SGGP volume calc

... % [optional block]

end volume %

read plot % SGGP Plots

... % [optional block]

end plot %

read definitions % Definitions

... % [possibly required]

end definitions %

read sources % Sources definition

... % [required block]

end sources %

read tallies % Tally specifications

... % [optional block]

end tallies %

read parameters % Monte Carlo parameters

... % [optional block]

end parameters %

read biasing % Biasing information

... % [optional block]

end biasing %

read importanceMap % Importance map

... % [optional block]

end importanceMap %

end data % end of all blocks

end % end of MAVRIC input

4.1.3.2. SGGP geometry blocks

MAVRIC uses the functional module Monaco for the forward Monte Carlo calculation. Monaco tracks particles through the physical geometry described by the SGGP input blocks, as well as through the mesh importance map and any mesh tallies, which are defined in the global coordinates and overlay the physical geometry. Because Monaco must track through all of these geometries at the same time, users should not use the reflective boundary capability in the SGGP geometry.

For more details on each SGGP geometry block, see the following sections of the KENO-VI chapter Sect. 8.1 of the SCALE Manual.

Geometry – Geometry Data

Array – Array Data

Volume – Volume Data

Plot – Plot Data

4.1.3.4. Importance map block

The importance map block is the “heart and soul” of MAVRIC. This block lists the parameters for creating an importance map and biased source from one (adjoint) or two (forward, followed by adjoint) Denovo discrete-ordinates calculations. Without an importance map block, MAVRIC can be used to run Monaco and use its conventional types of variance reduction. If both the importance map and biasing blocks are specified, then only the importance map block will be used. The various ways to use the importance map block are explained in the subsections below. Keywords for this block are summarized at the end of this section, in Table 4.1.4.

4.1.3.4.1. Constructing a mesh for the SN calculation

All uses of the importance map block that run the discrete-ordinates code require the use of a grid geometry that overlays the physical geometry. Grid geometries are defined in the definitions block of the MAVRIC input. The extent and level of detail needed in a grid geometry are discussed in the following paragraphs.

When using SN methods alone for solving radiation transport in shielding problems, a good rule of thumb is to use mesh cell sizes on the order of a meanfree path of the particle. In complex shielding problems, this could lead to an extremely large number of mesh cells, especially when considering the size of the meanfree path of the lowest energy neutrons and photons in common shielding materials.

In MAVRIC, the goal is to use the SN calculation for a quick approximate solution. Accuracy is not paramount-just getting an idea of the overall shape of the true importance map will help accelerate the convergence of the forward Monte Carlo calculation. The more accurate the importance map, the better the forward Monte Carlo acceleration will be. At some point there is a time trade-off when the computational time for calculating the importance map followed by the time to perform the Monte Carlo calculation exceeds that of a standard analog Monte Carlo calculation. Large numbers of mesh cells that result from using very small mesh sizes for SN calculations also use a great deal of computer memory.

Because the deterministic solution(s) for CADIS and FW-CADIS can have moderate fidelity and still provide variance reduction parameters that substantially accelerate the Monte Carlo solution, mesh cell sizes in MAVRIC applications can be larger than what most SN practioners would typically use. The use of relatively coarse mesh reduces memory requirements and the run time of the deterministic solution(s). Some general guidelines to keep in mind when creating a mesh for the importance map/biased source are as follows:

The true source regions should be included in the mesh with mesh planes at their boundaries.

Place point or very small sources in the center of a mesh cell, not on the mesh planes.

Any region of the geometry where particles could eventually contribute to the tallies (the “important” areas) should be included in the mesh.

Point adjoint sources (corresponding to point detector locations) in standard CADIS calculations do not have to be included inside the mesh. For FW-CADIS, they must be in the mesh and should be located at a mesh cell center, not on any of the mesh planes.

Volumetric adjoint sources should be included in the mesh with mesh planes at their boundaries.

Mesh planes should be placed at significant material boundaries.

Neighboring cell sizes should not be drastically different.

Smaller cell sizes should be used where the adjoint flux is changing rapidly, such as toward the surfaces of adjoint sources and shields (rather than in their interiors).

Another aspect to keep in mind is that the source in the forward Monaco Monte Carlo calculation will be a biased mesh-based source. Source particles will be selected by first sampling which mesh cell to use and then sampling a position uniformly within that mesh cell that meets the user criteria of “unit=”, “region=”, or “mixture=” if specified. The mesh should have enough resolution that the mesh source will be an accurate representation of the true source.

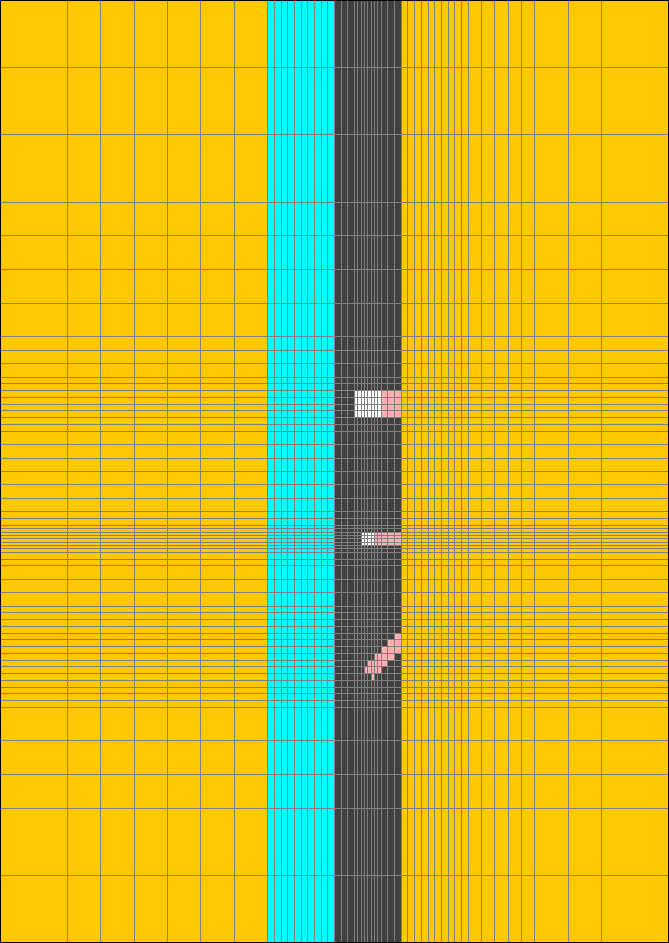

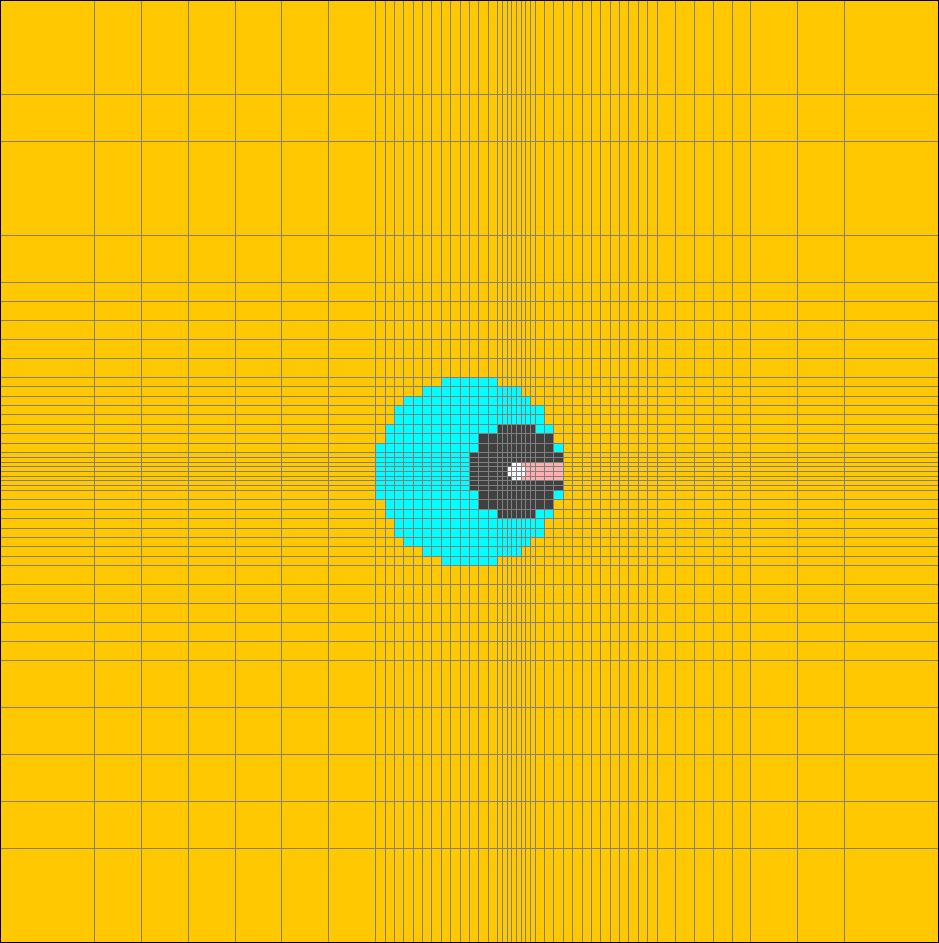

The geometry for the Denovo calculation is specified using the keyword “gridGeometryID=” and the identification number of a grid geometry that was defined in the definitions block. The material assigned to each voxel of the mesh is determined by testing the center point in the SGGP geometry (unless the macro-material option is used-see below).

4.1.3.4.2. Macromaterials for SN geometries

Part of the advantage of the CADIS method is that the adjoint discrete-ordinates calculation only needs to be approximate in order to form a reasonable importance map and biased source. This usually means that the mesh used is much coarser than the mesh that would be used if the problem were to be solved only with a discrete-ordinates code. This coarse mesh may miss significant details (especially curves) in the geometry and produce a less-than-optimal importance map.

To get more accurate solutions from a coarse-mesh discrete-ordinates calculation, Denovo can represent the material in each voxel of the mesh as a volume-weighted mixture of the real materials, called macromaterials, in the problem. When constructing the Denovo input, the Denovo EigenValue Calculation (DEVC, see section Sect. 2.4) sequence can estimate the volume fraction occupied by using each real material in each voxel by a sampling method. The user can specify parameters for how to sample the geometry. Note that finer sampling makes more accurate estimates of the material fraction but requires more setup time to create the Denovo input. Users should understand how the macromaterials are sampled and should consider this when constructing a mesh grid. This is especially important for geometries that contain arrays. Careful consideration should be given when overlaying a mesh on a geometry that contains arrays of arrays.

Because the list of macromaterials could become large, the user can also

specify a tolerance for how close two different macromaterials can be in order to

be considered the same, thereby reducing the total number of

macromaterials. The macromaterial tolerance, “mmTolerance=”, is used for

creating a different macromaterial from the those already created by

looking at the infinity norm between two macromaterials.

The number of macromaterials does not appreciably impact Denovo run time

or memory requirements.

Two different sampling methods are available-point testing [MAVRIC-IPE+09] with

the keyword mmPointTest and ray tracing [MAVRIC-Joh13] with the keyword

mmRayTest.

4.1.3.4.2.1. Ray Tracing

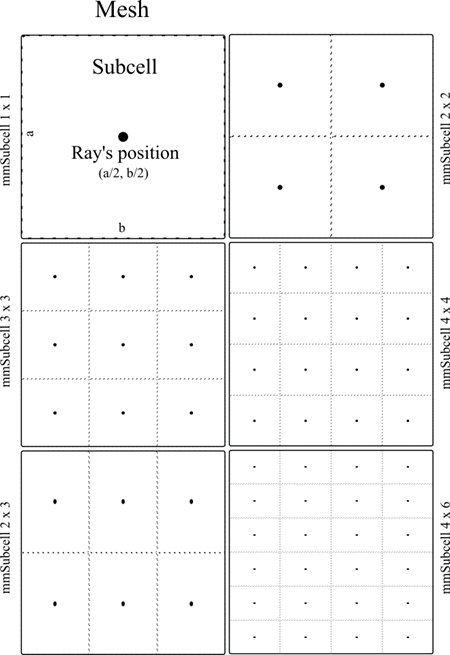

This method estimates the volume of different materials in the Denovo mesh grid elements by tracing rays through the SGGP geometry and computing the average track lengths through each material. Rays are traced in all three dimensions to better estimate the volume fractions of materials within each voxel. The mmSubCell parameter controls how many rays will be traced in each voxel in each dimension. For example, if mmSubCell= n, then when tracing rays in the z dimension, each column of voxels uses a set of n \(\times\) n rays starting uniformly spaced in the x and y dimensions. With rays being cast from all three orthogonal directions, a total of 3n2 rays are used to sample each voxel. One can think of subcells as an equally spaced sub-mesh with a single ray positioned at each center. The number of subcells in each direction, and hence the number of rays, can be explicitly given with mmSubCells ny nz nx nz nx ny end keyword for rays parallel to the x axis, y axis, and z axis. Fig. 4.1.1 shows different subcell configurations (in two dimensions) for a given voxel.

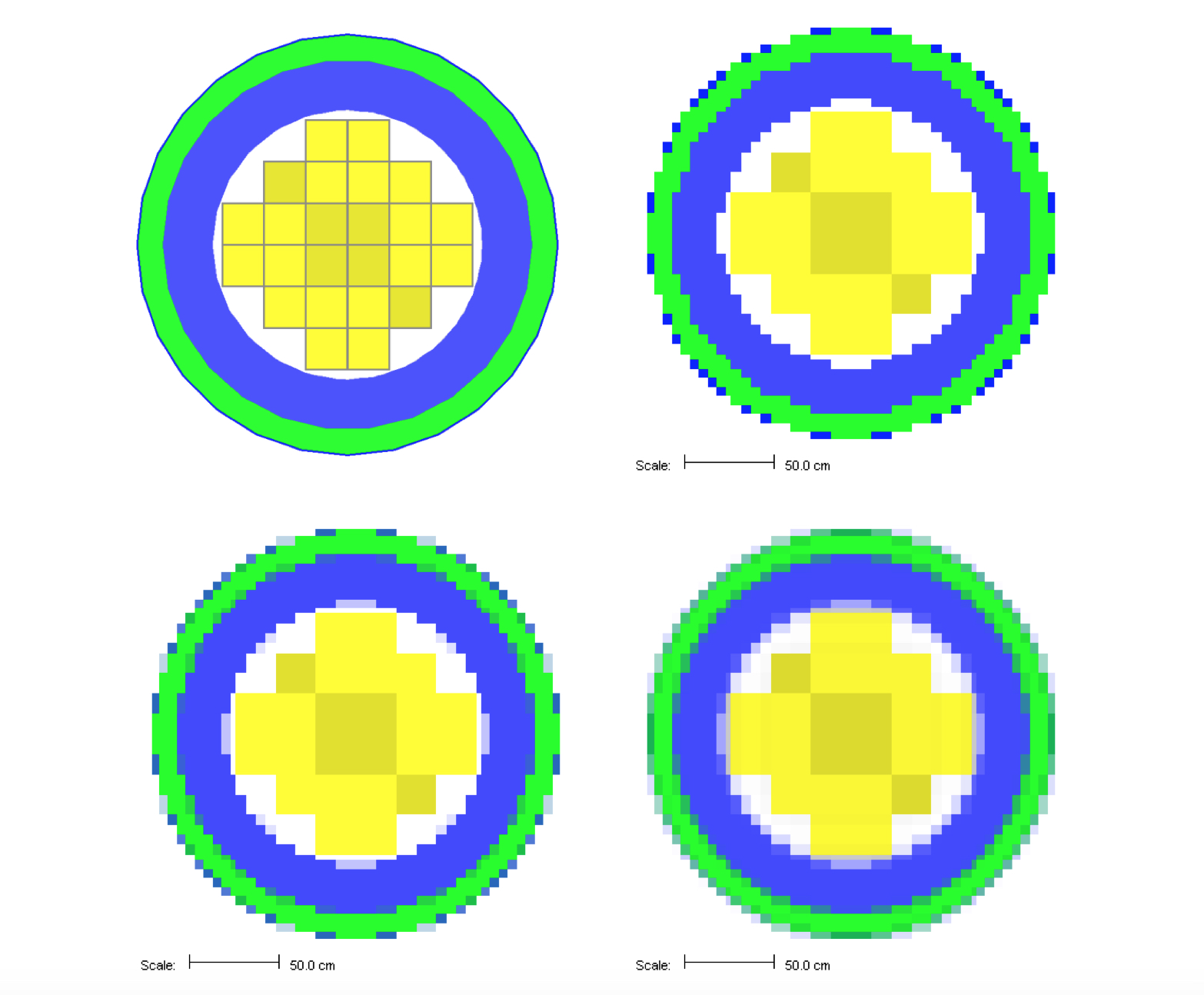

Fig. 4.1.1 Ray positions within a voxel with different mmSubCells parameters.

Ray tracing is a more robust method compared to the simple point testing method used in previous versions of SCALE/MAVRIC; however, it requires more memory than point testing. Ray tracing gives more accurate estimates of volume fractions because track lengths across a voxel give more information than a series of test points. Ray tracing is also much faster than point testing because the particle tracking routines are optimized to quickly determine lists of materials and distance along a given ray.

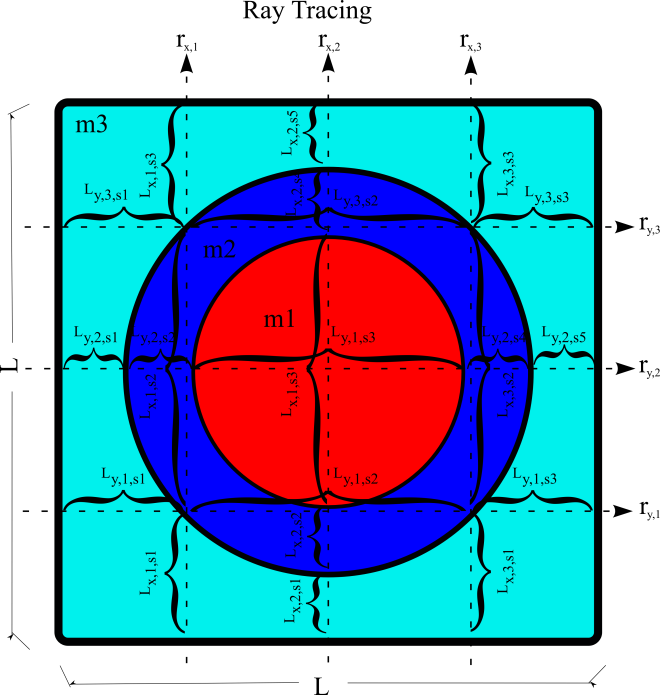

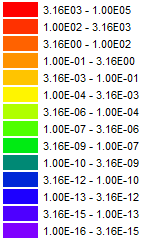

Ray tracing operates on the grid geometry supplied by the user and shoots rays in all three directions, starting from the lower bounds of the mesh grid. An example of an arbitrary assembly geometry is shown in Fig. 4.1.2. A ray consists of a number of steps that each correspond to crossing a material boundary along the path of the ray. Ratios of each step’s length to the voxel length in the ray’s direction determine the material volume fraction of that step in that voxel, and summation of the same material volume fractions gives the material volume fraction of that material in that voxel. Ray tracing through a single voxel that contains a fuel pin is illustrated in Fig. 4.1.3.

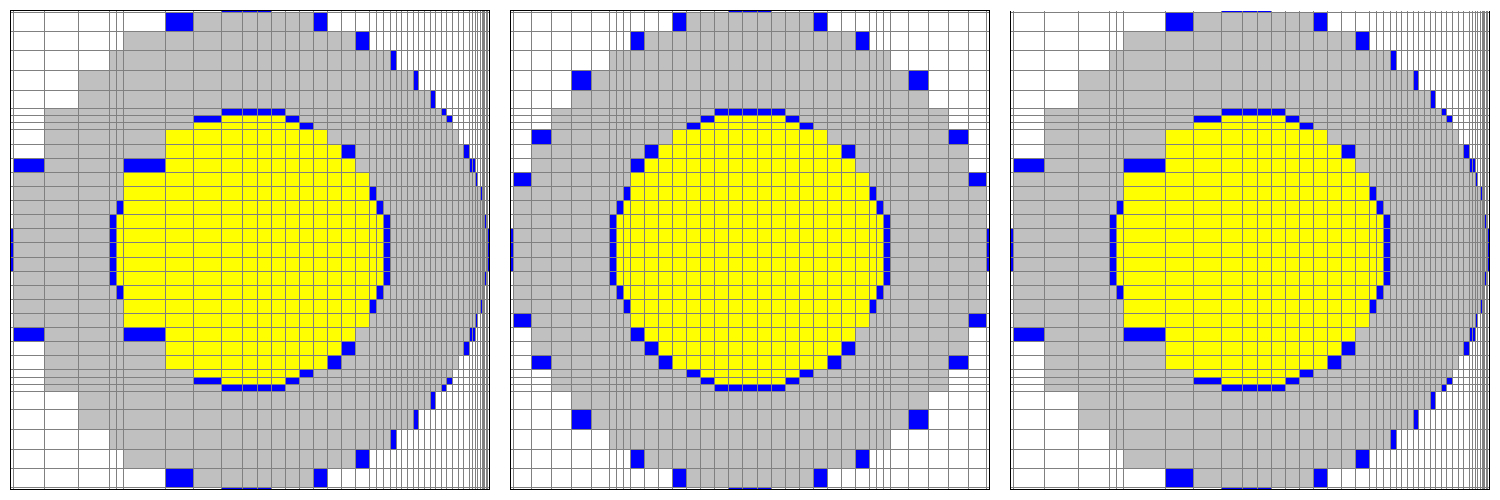

Fig. 4.1.2 Geometry model (left) and the Denovo representation (right) of an assembly using macromaterials determined by ray tracing.

Fig. 4.1.3 Ray tracing (in two dimensions) through a voxel.

The final constructed macromaterials for this model are also shown in Fig. 4.1.2. Voxels that contain only a single material are assigned the original material number in the constructed macromaterials. For the voxels that contain a fuel pin with three different materials, the result is a new macromaterial consisting of the volume weighted fractions of each original material.

After the rays are shot in all three directions, the material volume fractions are updated, and macromaterials are created by using these material volume fractions. Material volume fraction calculations for a single voxel, as shown in Fig. 4.1.3, are given by

where Fm = sampled fraction of material m in the voxel,

d = direction of the rays (x, y, z),

r = ray number,

\(N_r\) = total number of rays in the voxel for direction of d,

s = step number,

\(N_s\) = total number of steps for ray r in the voxel for direction of d,

\(L_{d,r,s}\) = length of the steps s for ray r in the voxel for direction of d,

\(L_d\) = length of the voxel along direction of d,

\(m_s\) = material of step s,

m = material number,

\(N_m\) = total number of materials in the voxel, and

\(V_m\) = volume fraction of material m in the voxel.

4.1.3.4.2.2. Point Testing

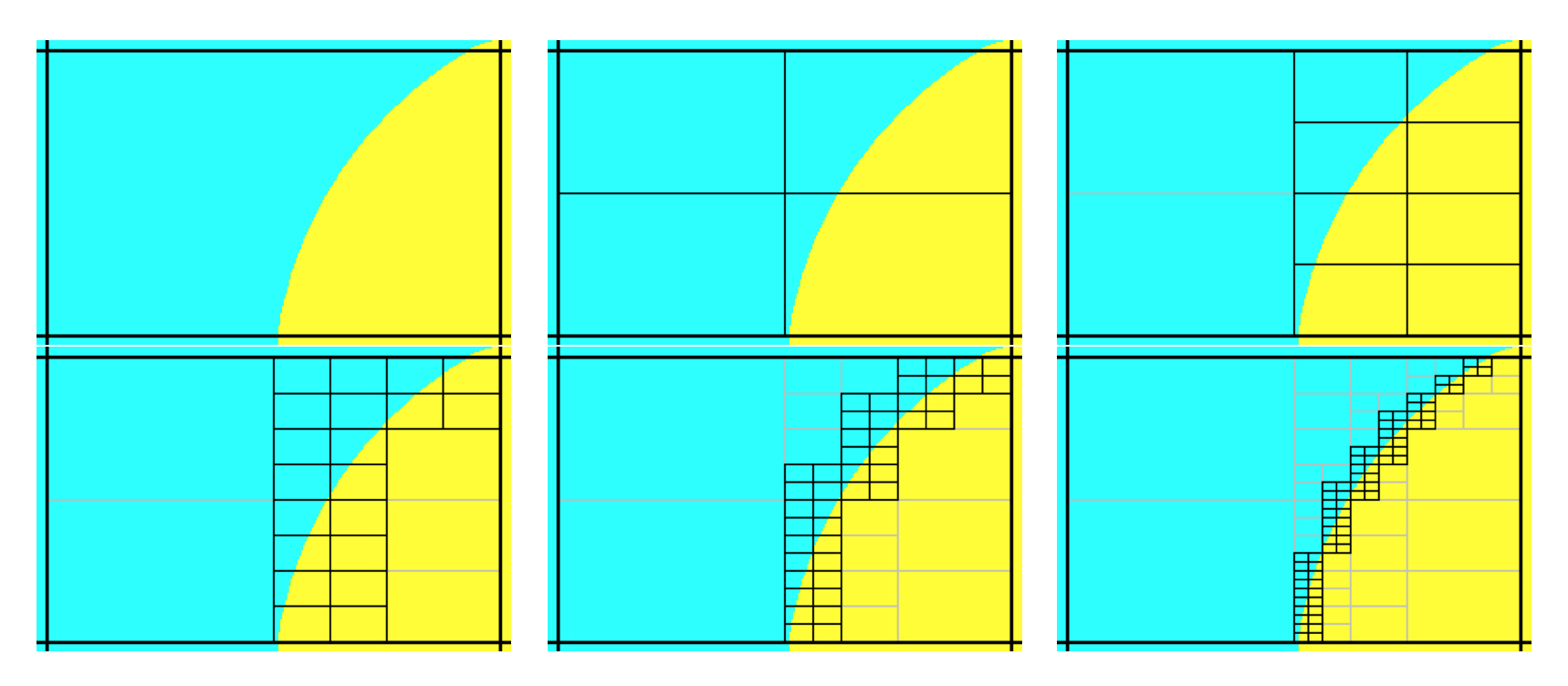

The recursive bisection method is utilized in point testing and uses a series of point tests to determine the macromaterial fractions. For a given voxel, the material at the center is compared to the material at the eight corners. If they are all the same, then the entire volume is considered to be made of that material. If they are different, then the volume is divided into two in each dimension. Each subvolume is tested, and the method is then applied to the subvolumes that are not of a single material. When the ratio of the volume of the tested region to the original voxel becomes less than a user-specified tolerance (in the range of 10-1 to 10-4), then further subdivision and testing are stopped. This is illustrated in Fig. 4.1.4.

Fig. 4.1.4 Recursive bisection method.

Fig. 4 Successive steps in the recursive macromaterial method

In point testing, the keyword “mmTolerance=f” is interpreted to be where f is the smallest fraction of the voxel volume that can be achieved by bisection method and hence the limiting factor for dividing the voxel. This same tolerance f is also used to limit the number of macromaterials. Before a new macromaterial is created, if one already exists where the fraction of each actual material matches to within the given tolerance, then the existing material will be used. If using only a single point at the center of each voxel, then use “mmTolerance=1”. The mmSubCell keyword is not used in point testing.

4.1.3.4.2.3. Example

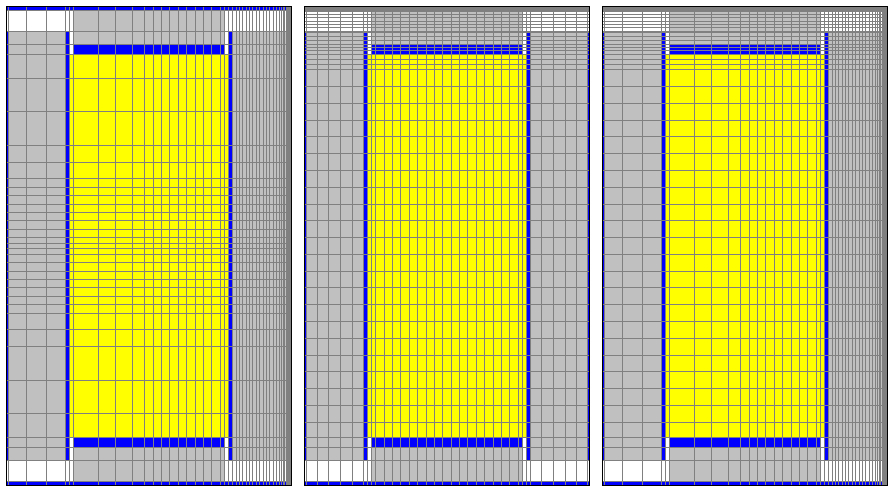

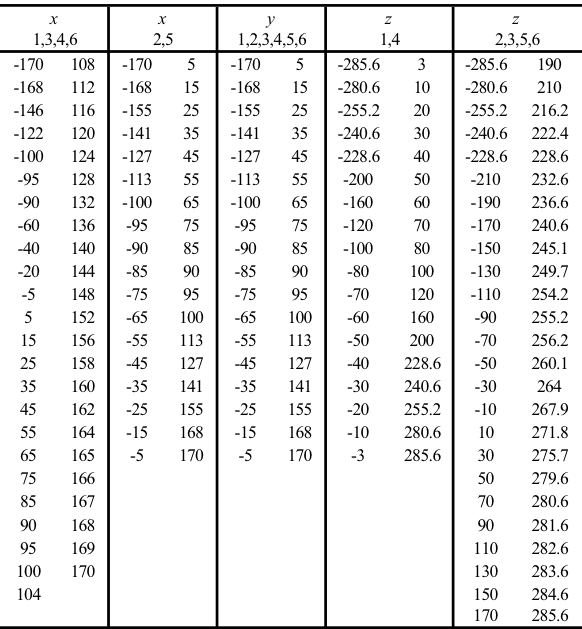

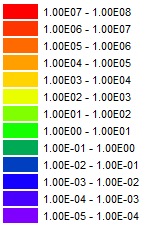

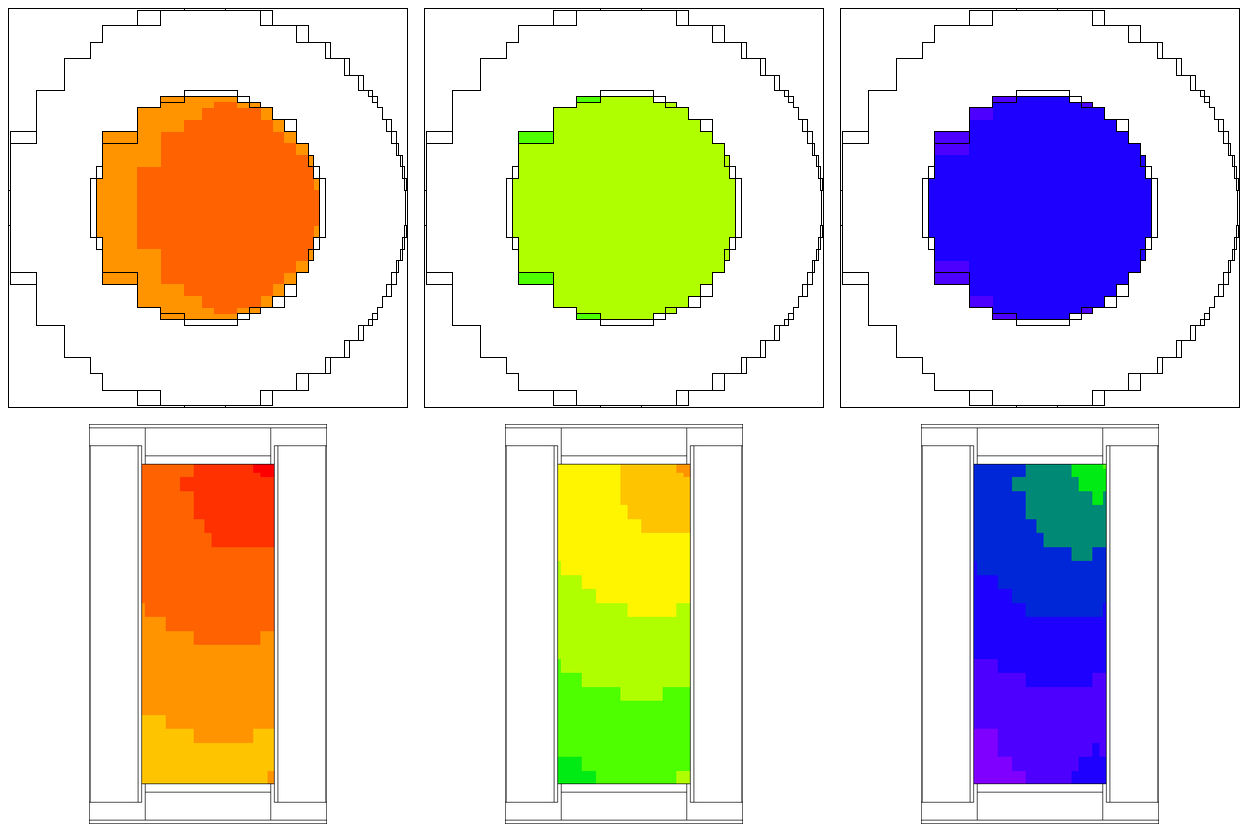

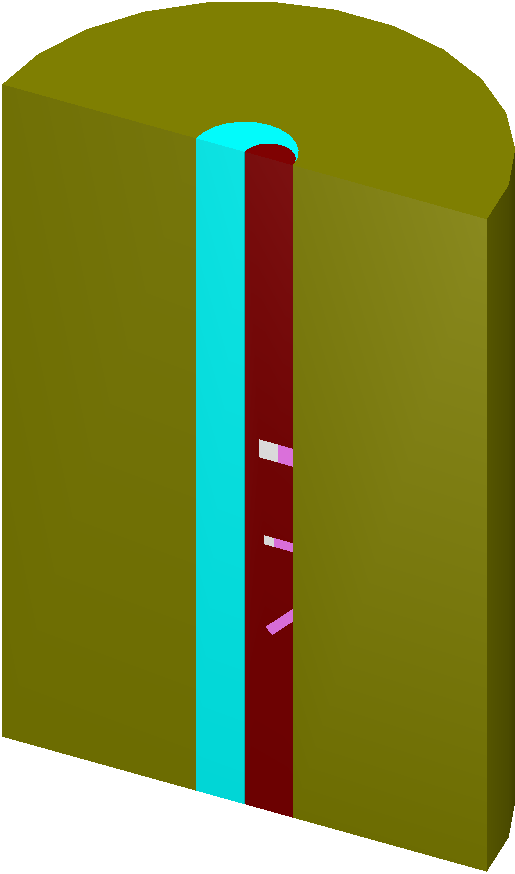

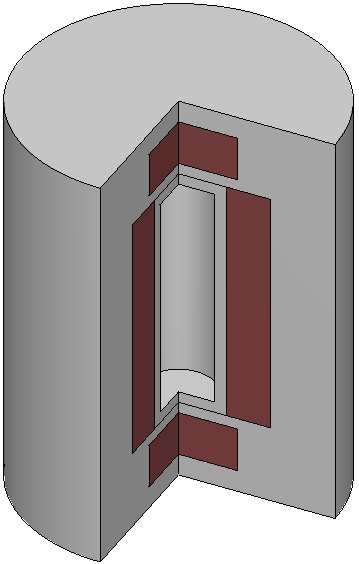

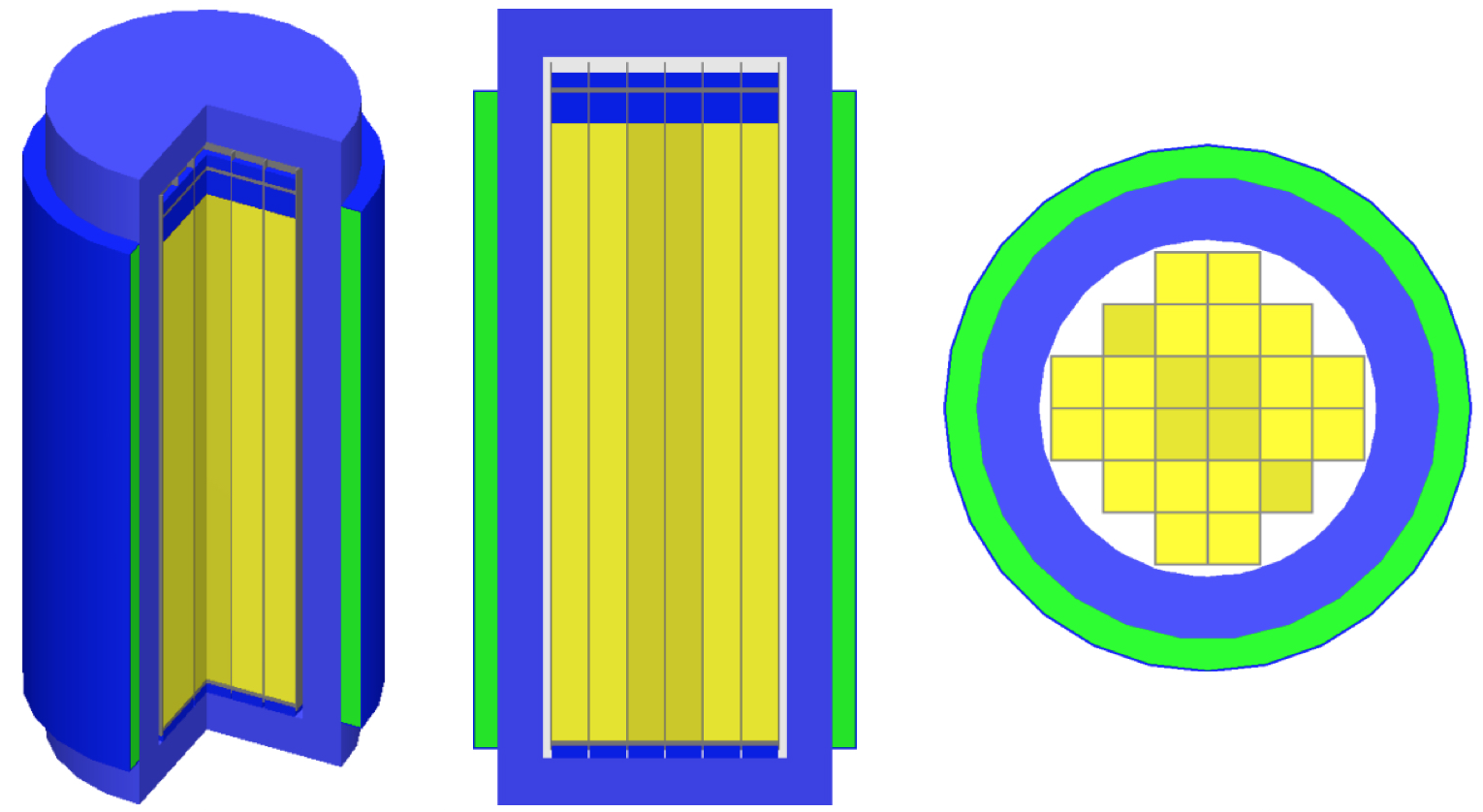

Fig. 4.1.5 shows an example of a cask geometry with two types of spent fuel (yellows), steel (blue), resin (green), and other metals (gray). When the Denovo geometry is set up by testing only the center of each mesh cell, the curved surfaces are not well represented (upper right). By applying the ray-tracing method and defining a new material made of partial fractions of the original materials, an improved Denovo model can be made. In the lower left of the figure, the Denovo model was constructed using one ray (in each dimension) per voxel and a tolerance of 0.1. This gives 20 new materials that are a mixture of the original 13 actual materials and void. With mmSubCells=3 and an mmTolerance=0.01, 139 macromaterials are created.

A macromaterial table listing the fractions of each macromaterial is saved to a file called “outputName.mmt”, where outputName is the name the user chose for his or her output file. This file can be used by the Mesh File Viewer to display the macromaterials as mixtures of the actual materials, as seen in the lower row of Fig. 4.1.5. See the Mesh File Viewer help pages for more information on how to use colormap files and macromaterial tables.

Fig. 4.1.5 Cask geometry model (upper left) and the Denovo representation using cell center testing (upper right). Representations using macromaterials determined by ray tracing are shown for mmSubCell=1/mmTolerance=0.1 (lower left) and mmSubCell=3/mmTolerance=0.01 (lower right).*

4.1.3.4.3. Optimizing source/detector problems

For standard source/detector problems in which one tally is to be optimized in the forward Monte Carlo calculation, an adjoint source based on that tally must be constructed. An adjoint source requires a unique and positive identification number, a physical location, and an energy spectrum. The adjoint source location can be specified either by (1) a point location (“locationID=” keyword) or (2) a volume described by a box (“boundingBox” array). A bounding box is specified by maximum and minimum extent in each dimension-\(x_{max}\) \(x_{min}\) \(y_{max}\) \(y_{min}\) \(z_{max}\) \(z_{min}\)-in global coordinates. The boundingBox should not be degenerate (should have volume>0) but can be optionally limited to areas matching a given unit number (“unit=”), a given region number (“region=”), or a given material mixture number (“mixture=”). A mixture and a region cannot both be specified, since that would either be redundant or mutually exclusive. The energy spectrum of an adjoint source is a response function (“responseID=”) listing one of the ID numbers of the responses defined in the definitions block. An optional weight can be assigned to each adjoint source using the “weight=” keyword. If not given, the default weight is 1.0.

For example, to optimize a region tally, the user would construct an adjoint source located in the same place as the tally, with an adjoint source spectrum equal to the response function that the tally is computing. Note that the grid geometry 1 and response function 3 must already be defined in the definitions block.

read importanceMap

gridGeometryID=1

adjointSource 24

boundingBox 12.0 10.0 5.0 -5.0 10.0 -10.0

unit=1 region=5

responseID=3

end adjointSource

end importanceMap

For optimizing a point detector for the calculation of total photon flux, the importance map block would look like the following:

read importanceMap

adjointSource 21

locationID=4

responseID=1

end adjointSource

gridGeometryID=1

end importanceMap

where location 4 is the same location used by the point detector. To calculate total photon flux, response function 1 must be defined in the definitions block similar to this response:

read definitions

response 1

values 27r0.0 19r1. end

end response

…

end definitions

This response is used for computing total photon flux for the 27 neutron/19 photon group coupled cross section library or like this response

read definitions

response 1

photon

bounds 1000.0 2.0e7 end

values 1.0 1.0 end

end response

…

end definitions

which is independent of the cross section library.

4.1.3.4.4. Multiple adjoint sources

If there are several tallies in very close proximity and/or several different responses being calculated by the tallies, multiple adjoint sources can be used.

read importanceMap

gridGeometryID=1

adjointSource 1

locationID=4 responseID=20

end adjointSource

adjointSource 2

locationID=5 responseID=21

weight=2.0

end adjointSource

end importanceMap

Note that adjoint sources using point locations can be mixed with volumetric adjoint sources (using bounding boxes).

4.1.3.4.5. Options for Denovo \(S_n\) calculations

While the default values for various calculational parameters and settings used by Denovo for the MAVRIC sequence should cover most applications, they can be changed if desired. The two most basic parameters are the quadrature set used for the discrete ordinates and the order of the Legendre polynomials used in describing the angular scattering. The default quadrature order that MAVRIC uses is a level symmetric \(S_8\) set, and the default scattering order is \(P_3\) (or the maximum number of coefficients contained in the cross-section library if less than 3). \(S_8\)/ \(P_3\) is an adequate choice for many applications, but the user is free to changes these. For complex ducts or transport over large distances at small angles, \(S_{12}\) may be required. \(S_4\)/ \(P_1\) or even \(S_2\)/ \(P_0\) would be useful in doing a very cursory run to confirm that the problem was input correctly, but this would likely be inadequate for weight window generation in a problem that is complex enough to require advanced variance reduction.

These and other Denovo options are applied to both the forward and the adjoint calculations that are required from the inputs given in the importance map block.

In problems with small sources or media that are not highly scattering, discrete ordinates can suffer from “ray effects” [MAVRIC-Lat71, MAVRIC-Lat68] where artifacts of the discrete quadrature directions can be seen in the computed fluxes. Denovo has a first-collision capability to help alleviate ray effects. This method computes the uncollided flux in each mesh cell from a point source. The uncollided fluxes are then used as a distributed source in the main discrete-ordinates solution. At the end of the main calculation, the uncollided fluxes are added to the fluxes computed with the first collision source, forming the total flux. While this helps reduce ray effects in many problems, the first-collision capability can take a significant amount of time to compute on a mesh with many cells or for many point sources.

Adjoint sources that use point locations will automatically use the Denovo first-collision capability. Volumetric adjoint sources (that use a boundingBox) will be treated without the first-collision capability. The keywords “firstCollision” and “noFirstCollision” will be ignored by MAVRIC for adjoint calculations. Keywords for Denovo options in the importance map block are summarized at the end of this section, in Table 4.1.5.

4.1.3.4.6. Starting with an existing adjoint flux file

An importance map can be made from an existing Denovo flux file by using the keyword “adjointFluxes=” with the appropriate file name in quotes. The file must be a binary file using the *.dff file format, and the number of groups must match the number of groups in the MAVRIC cross section library (i.e., the library entered on the third line of the MAVRIC input file). Instead of performing an adjoint calculation, the fluxes read from the file will be used to create both the mesh-based importance map and the biased mesh source.

read importanceMap

adjointFluxes="c:\mydocu~1\previousRun.adjoint.dff"

gridGeometry=7

end importanceMap

If the “adjointFluxes=” keyword is used and any adjoint sources are defined, an error will result. If a forward flux file is supplied for forward-weighting the adjoint source (see below), then an adjoint flux file cannot be specified.

The grid geometry is not required when using a pre-existing flux file. If grid geometry is not supplied, one will be created from the mesh planes that are contained in the Denovo flux file (which were used to compute the fluxes in that file).

4.1.3.4.7. Forward-weighting the adjoint source

To optimize a mesh tally or multiple region tallies/point detector tallies over a large region, instead of a uniform weighting of the adjoint source, a weighting based on the inverse of the forward response can be performed. This requires an extra discrete-ordinates calculation but can help the forward Monte Carlo calculation compute the mesh tally or group of tallies with more uniform statistical uncertainties.

The same grid geometry will be used in both the forward calculation and the adjoint calculation, so the user must ensure that the mesh covers all of the forward sources and all of the adjoint sources, even if they are point sources.

To use forward-weighted CADIS, specify either of the keywords — “respWeighting” or “fluxWeighting”. For either, MAVRIC will run Denovo to create an estimate of the forward flux, \(\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\). For response weighting (“respWeighting”), each adjoint source is inversely weighted by the integral of the product of the response function used in that adjoint source and the estimate of the forward flux. For an adjoint source described by the geometric function \(g(\overrightarrow{r})\) and the response function \(\sigma_{d}\left( E \right)\) (note that \(\sigma_{d}\left( E \right) = 1\) for computing total fluxes), the forward-weighted adjoint source becomes

Response weighting will calculate more uniform relative uncertainties of the integral quantities of the tallies in the final Monte Carlo calculation.

To optimize the calculation of the entire group-wise flux with more uniform relative uncertainties in each group, the adjoint source should be weighted inversely by the forward flux, \(\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right),\) using the “fluxWeighting” keyword. For an adjoint source described by the geometric function \(g(\overrightarrow{r})\) and the response function \(\sigma_{d}\left( E \right) = 1\), the forward-weighted adjoint source becomes

For example, consider a problem with a single source and two detectors, one near the source that measures flux and one far from the source that measures some response. In a standard Monte Carlo calculation, it is expected that since more Monte Carlo particles cross the near detector, it will have a much lower relative uncertainty than the far detector. Standard CADIS could be used to optimize the calculation of each in separate simulations:

To optimize the flux in the near detector:

read importanceMap

gridGeometryID=1

adjointSource 1

boundingBox x1 x2 y1 y2 z1 z2

responseID=1

end adjointSource

end importanceMap

To optimize the response in the far detector:

read importanceMap

gridGeometryID=1

adjointSource 2

boundingBox u1 u2 v1 v2 w1 w2

responseID=6

end adjointSource

end importanceMap

where response 1 was defined as \(\sigma_{1}\left( E \right) = 1\) and response 6 was defined as \(\sigma_{6}\left( E \right) =\) flux-to-response conversion factors. The two options for forward weighting allow the tallies for both detectors to be calculated in the same MAVRIC simulation. Using “fluxWeighting”, the importance map and biased source will be made to help distribute Monte Carlo particles evenly through each energy group and every voxel in both detectors, making the relative uncertainties close to uniform. With “respWeighting”, the importance map and biased source will optimize the total integrated response of each tally.

To optimize \(\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)\) in each detector

read importanceMap

gridGeometryID=1

' near detector

adjointSource 1

boundingBox x1 x2 y1 y2 z1 z2

responseID=1

end adjointSource

' far detector

adjointSource 2

boundingBox u1 u2 v1 v2 w1 w2

responseID=6

end adjointSource

fluxWeighting

end importanceMap

To optimize a total response \(\int_{}^{}{\sigma_{d}\left ( E \right) \phi \left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)} dE\) (either total flux or total dose)

read importanceMap

gridGeometryID=1

' near detector

adjointSource 1

boundingBox x1 x2 y1 y2 z1 z2

responseID=1

end adjointSource

' far detector

adjointSource 2

boundingBox u1 u2 v1 v2 w1 w2

responseID=6

end adjointSource

respWeighting

end importanceMap

Using flux weighting, the adjoint source will be

(4.1.21)\[q^{+}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right) = \frac{\sigma_{1}\left( E \right)g_{\mathrm{\text{near}}}(\overrightarrow{r})}{\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)} + \frac{\sigma_{6}\left( E \right)g_{\mathrm{\text{far}}}(\overrightarrow{r})}{\phi\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\ ,\]

or using response weighting, the adjoint source will be

(4.1.22)\[q^{+}\left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right) = \frac{\sigma_{1}\left( E \right)g_{1}(\overrightarrow{r})}{\int_{}^{}{\sigma_{1}\left( E \right)\phi \left(\overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\ dE} + \frac{\sigma_{6}\left( E \right)g_{2}(\overrightarrow{r})}{\int_{}^{}{\sigma_{6}\left(E \right)\phi \left( \overrightarrow{r},E \right)}\ dE} \ .\]

This implementation is slightly different from the original MAVRIC in SCALE 6. The current approach is simpler for the user and allows the importance parameters to optimize the final Monte Carlo calculation for the calculation of two different responses in two different areas.

If the number of mesh cells containing the true source is less than 10, then MAVRIC will convert these source voxels to point sources and Denovo will automatically use its first-collision capability to help reduce ray effects in the forward calculation. The user can easily override the MAVRIC defaults-to force the calculation of a first-collision source no matter how many voxels contain source; this can be done by using the keyword “firstCollision”. To prevent the calculation of a first-collision source, the keyword “noFirstCollision” can be used. If the keywords “firstCollision” or “noFirstCollision” are used, then they will only apply to the forward calculation, not the subsequent adjoint calculation.

The keyword “saveExtraMaps” will save extra files that can be viewed by the Mesh File Viewer. The source used by the forward Denovo calculation is stored in “outputName.dofs.3dmap”, where outputName is the name the user chose for his output file.

4.1.3.4.8. Forward weighting with an existing forward flux file

Similar to the capability of using pre-existing adjoint flux files, MAVRIC can use a pre-existing forward flux file to create a forward-weighted adjoint source without performing the forward Denovo calculation. The user may specify the *.dff file containing the forward fluxes using the keyword “forwardFluxes=”. The filename should be enclosed in quotes, and the file must be a binary file using the Denovo flux file format. The number of groups must match the number of groups in the MAVRIC cross section library (i.e., the library entered on the third line of the MAVRIC input file).

read importanceMap

forwardFluxes="c:\mydocu~1\previousRun.forward.dff"

gridGeometry=7

adjointSource 1

...

end adjointSource

respWeighting

end importanceMap

When using a pre-existing forward flux file, either “respWeighting” or “fluxWeighting” must still be specified.

4.1.3.4.9. Using the importance map

An importance map produced by the importance map block consists of the target weight values as a function of position and energy. The upper weight window used for splitting and the lower weight window used for Russian roulette are set by the window ratio. The window ratio is simply the ratio of the weight window’s upper bound to the weight window lower bound, with the target weight being the average of the upper and lower bounds.

The keyword “windowRatio=” can be used within the importance map block to specify what window ratio will be used with the importance map that is passed to the Monaco forward Monte Carlo calculation. For a windowRatio of \(r\), the upper weights for splitting, \(w_{max}\), and the lower weights for Russian roulette, \(w_{min}\), are set as

and

for the target weight \(\overline{w}\) in each mesh cell and for each energy of the importance map. The default value for the windowRatio is 5.0.

4.1.3.4.10. Other notes on importance map calculations

Since the importance map calculations all take place using mesh geometry, one of the first steps that occurs is to create a mesh representation of the true source (the forward source) on the same grid. This procedure uses the same two methods as the Monaco mesh source saver routine. Mesh cells can be subdivided and tested to see if they are within the defined source, or a set number of points can be sampled from the source. The keywords “subCells=” and “sourceTrials=” are used in the importance map block to change the default settings for constructing the mesh representation of the forward source.

If macromaterials are used (“mmTolerance<1”) and the adjoint source is limited to a particular material, then the amount of adjoint source in a mesh voxel will be weighted by the material amount in that voxel.

In SCALE/MAVRIC, Denovo is called as a fixed-source SN solver and cannot model multiplying media. Neither forward nor adjoint neutron calculations from Denovo will be accurate when neutron multiplication is a major source component. If neutron multiplication is not turned off in the parameters block of the MAVRIC input (using “fissionMult=0”), a warning will be generated to remind the user of this limitation.

By default, MAVRIC instructs Denovo not to perform outer iterations for neutron problems if the cross section library contains upscatter groups. This is because the time required calculating the fluxes using upscatter can be significantly longer than without. For problems in which thermal neutrons are an important part of the transport or tallies, the user should specify the keyword “upScatter=1” in the importance map block. This will instruct Denovo to perform the outer iterations for the upscatter groups, giving more accurate results but taking a much longer time for the discrete-ordinates calculation.

When performing a MAVRIC calculation using a coarse-group energy structure for Denovo (for example with the 27/19 library) but a fine-group energy structure (with the 200/47 library) for the final Monaco calculation, the source biasing parameters are determined on the coarse-group structure. The importance map (.mim) file and the biased mesh source (.msm) files all use the coarse-group structure. The source biasing information is then applied to fine-group mesh versions of the sources, resulting in the *.sampling.*.msm files. This way, the biased sources used in the final Monaco calculation retain their fine-group resolution. This can be especially important in representing the high-energy portion of the fission neutron distribution for example. When using CE-Monaco, the source sampling routines first use the *.msm files to determine the source particle’s voxel and energy group. From that voxel and energy group, the user-given source distributions are used to sample the specific starting location and specific energy of the source particle. This way, the CE-Monaco calculation samples the true CE distributions.

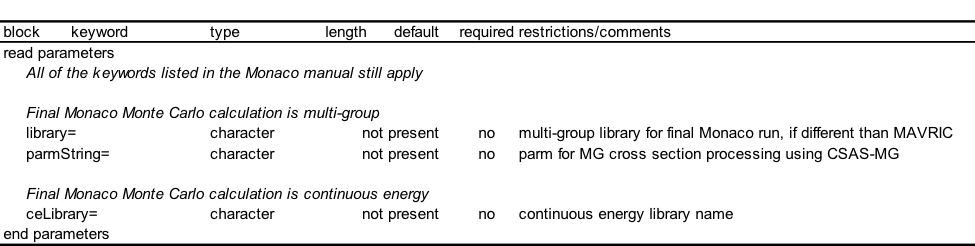

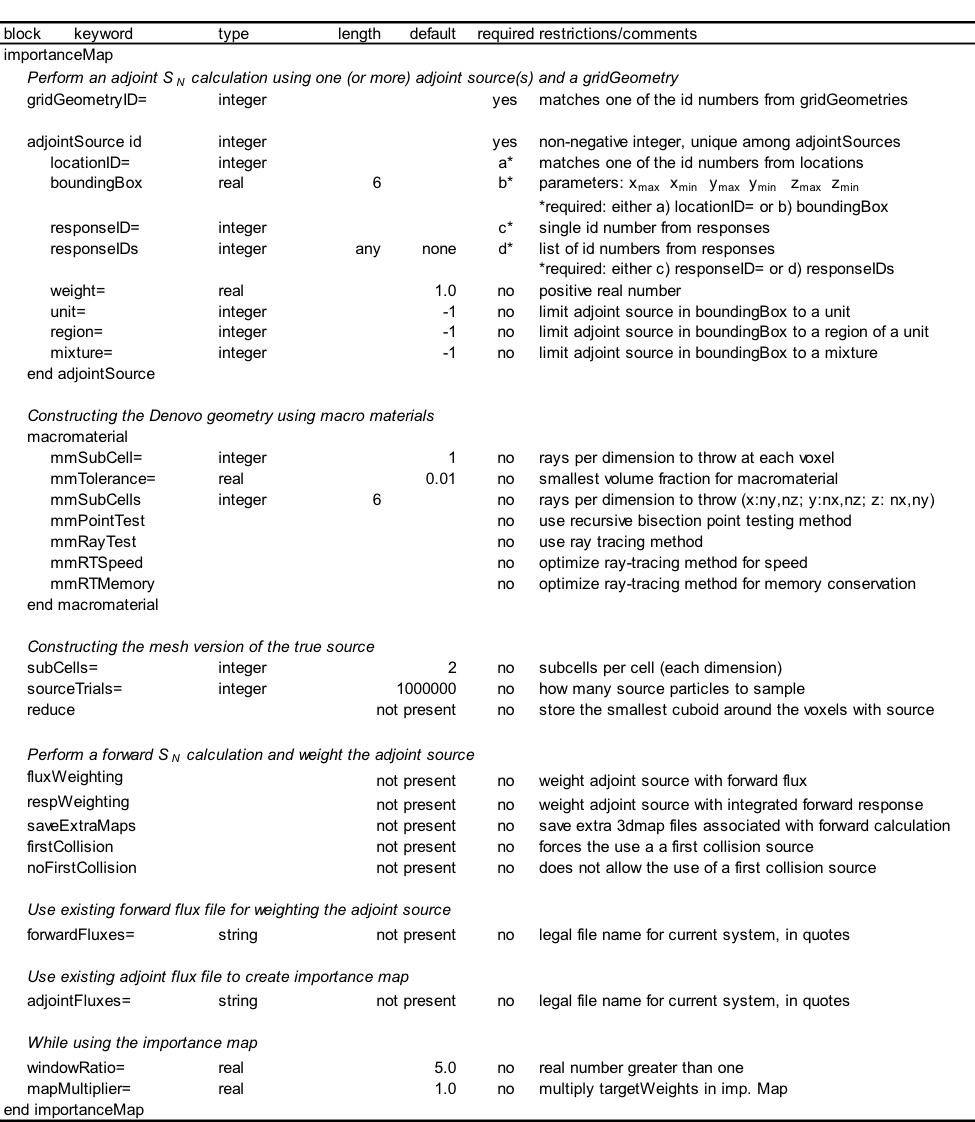

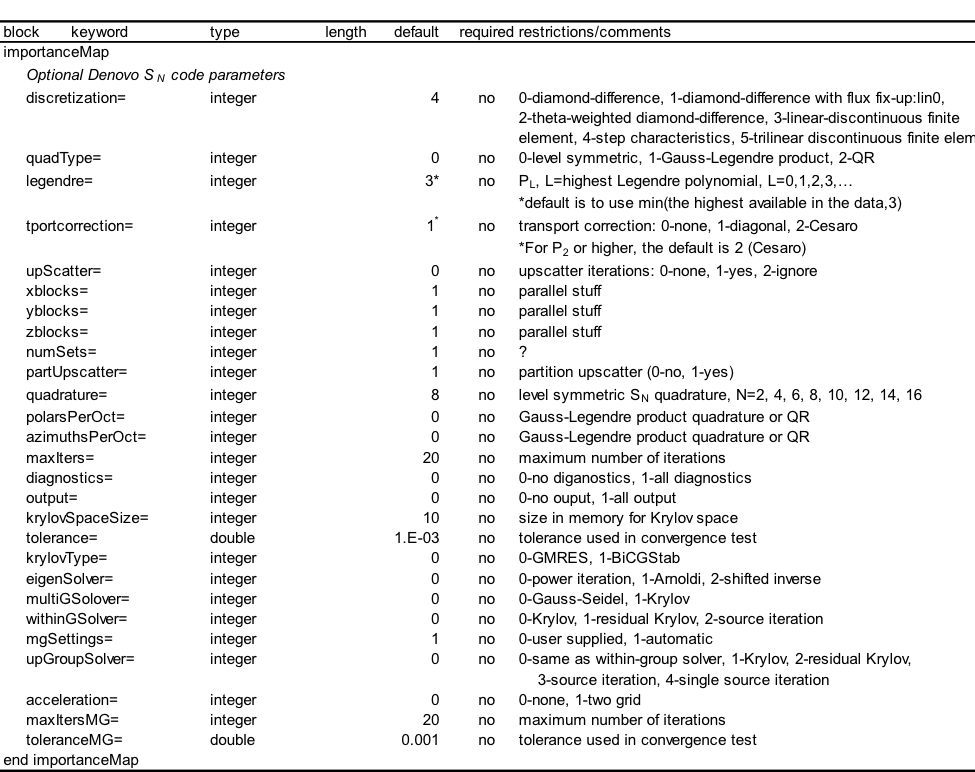

|

|

4.1.4. MAVRIC output

4.1.4.1. Main text output file

Similar to other SCALE sequences, MAVRIC returns a text output file containing the output from the SCALE driver, the sequence itself, and all of the functional modules called. The SCALE driver output first displays the problem input file, and then the first reading of the input file by the MAVRIC sequence is shown (which includes some material processing information). If there are any errors or warnings about the input file, they will be shown next. Next in the output file are the different passes through the MAVRIC sequence—up to 10 parts. If any errors or warning messages (such as lack of memory) are generated during processing, they will be displayed here. Finally, the output files from each functional module are concatenated to the above output and shows the files returned to the user.

First, the Monaco section of output first reviews the input it received. First the geometry is reviewed, showing which materials are used in each region and the volume of that region, if input or calculated. Then a detailed list of other Monaco input is reviewed: cross section parameters, data definitions, the source description, the tallies, the Monte Carlo parameters, and the biasing parameters. For MAVRIC calculations, if an importance map is used, then its summary is also given. The “Mesh Importance Map Characterization” shows where the importance map may be changing too rapidly and may require more refinement.

For each Monaco batch, the output file lists the batch time and the starting random number for the next batch, which may be useful in rerunning only a portion of a problem. Once all of the batches are completed, a list of the various tally files that have been created is given. Finally, the tallies are summarized in a section entitled “Final Tally Results Summary.” For each point detector, the total neutron and photon fluxes (uncollided and total) are given as well as the final response values for each response function. For each region tally, the total neutron and photon fluxes (both track-length and collision density estimates) are listed, followed by the final response values for each response function. Group-by-group details are saved to separate files for each tally.

4.1.4.2. Additional output files

In addition to the generous amount of data contained in the MAVRIC text output file, many other files are created containing the intermediate data used by the sequence and the final tally data. Many of the files produced can be viewed using the Mesh File Viewer or the Interactive Plotter capabilities of Fulcrum, which is distributed with SCALE. (Note that most of the images in this document were taken from the Mesh File Viewer from SCALE 6.1.) Table 4.1.6 lists the other output files, based on the name of the main output file (here called outputName), that are available to the user. These files will be copied back to the directory where the input file was located. Many of the files come from Monaco and are discussed in the Monaco chapter of the SCALE manual (Sect. 8.2).

Other files that the user may be interested in are listed in

Table 4.1.7. These files are kept in the temporary directory where SCALE

executes and are not copied back to the directory where the input file

was located, unless specifically requested using a SCALE “shell”

command. Curious users may also be interested in viewing the various

input files (i_*) that the MAVRIC sequence writes in order to run the

SCALE functional modules.

Filename |

Viewer |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Output Summary |

||

outputName.out |

main text output file, contains results summary |

|

Diagnostic files |

||

outputName.respid.chart |

P |

response input and MG representation for response id |

outputName.gridid.3dmap |

V |

mesh version of geometry using grid geometry id |

outputName.cylid.3dmap |

V |

mesh version of geometry using cylindrical geometry id |

outputName.distid.chart |

P |

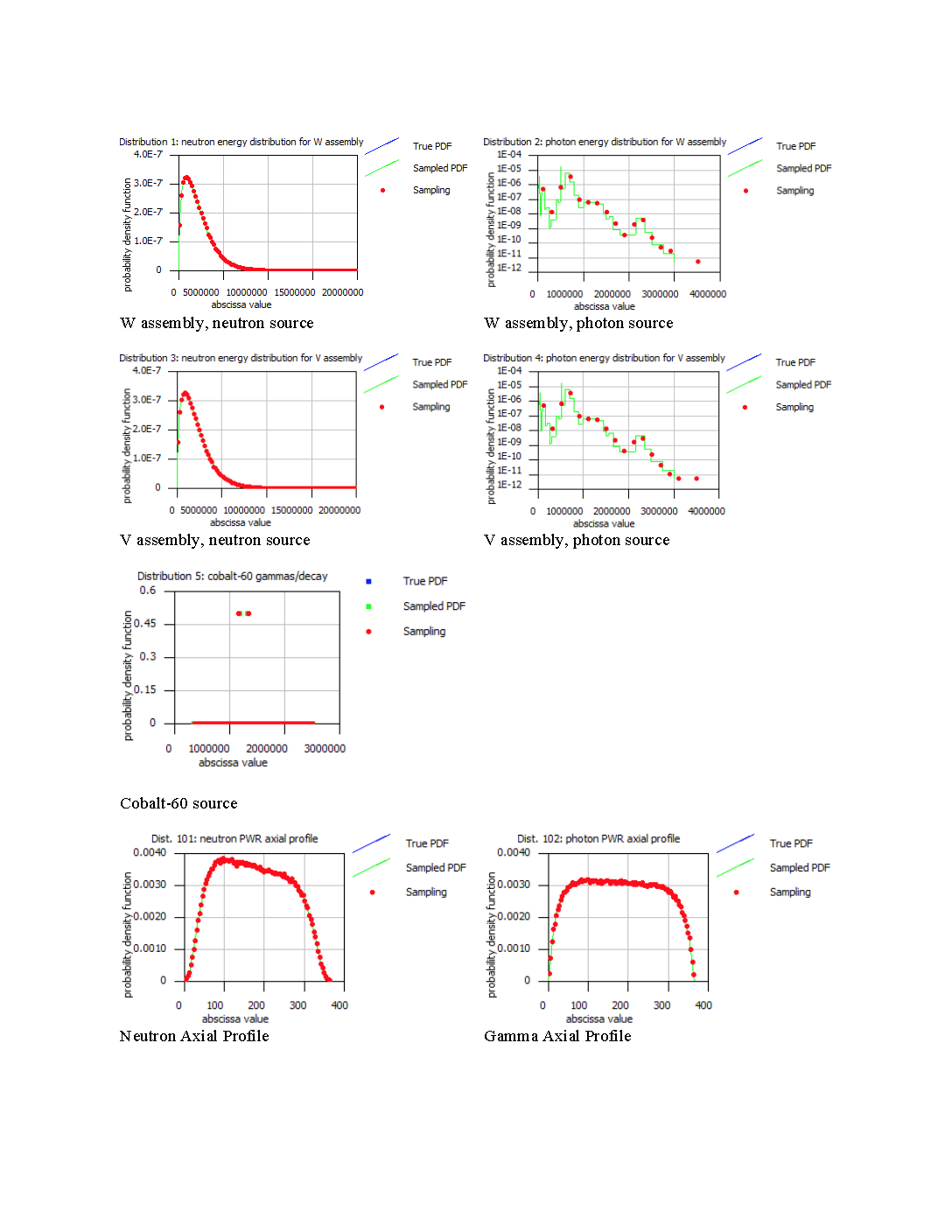

distribution input and sampling test for distribution id |

Mesh Source Saver |

||

filename.msm |

V |

mesh representation of a single source or total source |

filename.id.msm |

V |

mesh representation of multiple sources |

filename.sampling.msm |

V |

biased representation of a single source or total source |

filename.sampling.id.msm |

V |

biased representation of multiple sources |

Importance Map Generation |

||

outputName.geometry.3dmap |

V |

voxelized geometry (cell-center testing only) |

outputName.forward.dff |

V |

scalar forward flux estimate, \(\phi\left(x,y,z,E \right)\) |

outputName.adjoint.dff |

V |

scalar adjoint flux estimate, \(\phi^{+} \left( x,y,z,E \right)\) |

outputName.mim |

V |

Monaco mesh importance map, \(\overline{w}\left(x,y,z,E \right)\) |

outputName.msm |

V |

Monaco mesh source, \(\widehat{q}\left(x,y,z,E \right)\) |

outputName.mmt |

V |

macro-material table |

Tally Files |

||

outputName.pdid.txt |

detailed results for point detector tally id |

|

outputName.pdid.chart |

P |

batch convergence data for point detector tally id |

outputName.rtid.txt |

detailed results for region tally id |

|

outputName.rtid.chart |

P |

batch convergence data for region tally id |

outputName.mtid.3dmap |

V |

mesh tally for meshTally id |

outputName.mtid.respxx.3dmap |

V |

mesh tally of response by group for meshTally id response xx |

outputName.mtid.flux.txt |

detailed results for the group-wise flux of meshTally id |

|

outputName.mtid.tfluxtxt |

detailed results for total flux of meshTally id |

|

outputName.mtid.respxx.txt |

detailed results for response xx of meshTally id |

|

a V – can be displayed with the Mesh File Viewer capabilities of Fulcrum. P – can be displayed with the 2D plotting capabilities of Fulcrum.

Filename |

Description |

|---|---|

ft02f001 |

AMPX formatted cross sections for Denovo |

fort.51 |

text file, listings of the mixing table for Monaco |

fort.52 |

text file, review of MAVRIC sequence input variables |

fort.54 |

energy bin boundaries for the current cross section library |

xkba_b.inp |

binary input file for Denovo - rename to have a *.dsi extension (Denovo simple input) to be viewed via Mesh File Viewer |

4.1.5. Sample problems

4.1.5.1. Graphite shielding measurements with CADIS

As shown in the Monaco sample problem for simulating the Ueki shielding experiments (Monaco chapter Graphite Shielding Measurements) (Sect. 8.2.5.4), as the amount of shielding material between a source and detector increases, the time required to reach a certain level of relative uncertainty increases quickly. This example will use the MAVRIC automated variance reduction capability to optimize the calculation of the dose rate at the detector location by specifying an importance map block with an adjoint source made from the detector response function and the detector location.

4.1.5.1.1. Input file

The following is a listing of the file mavric.graphiteCADIS.inp located

in the SCALE samples\input directory. This calculation will use the

coarse-group shielding library (27n19g) for all of the importance map

calculations and the fine-group library (200n47g) for the final Monaco

step. Additions, compared to the file monaco.graphite.inp, include a

grid geometry for the Denovo computational mesh, a mesh tally to better

visualize the particle flow, and the importance map block to optimize

the Monte Carlo calculation of the point detector.

=mavric

Monaco/MAVRIC Training - Exercise 3. Graphite Shielding Measurements Revisited

v7-27n19g

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

' Composition Block - standard SCALE input

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

read composition

para(h2o) 1 1.0 293.0 end

carbon 2 den=1.7 1.0 300.0 end

end composition

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

' Geometry Block - SCALE standard geometry package (SGGP)

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

read geometry

global unit 1

cuboid 1 25.0 -25.0 25.0 -25.0 25.0 -25.0

cone 2 10.35948 25.01 0.0 0.0 rotate a1=-90 a2=-90 a3=0

cuboid 3 90.0 70.0 40.0 -40.0 40.0 -40.0

cuboid 99 120.0 -30.0 50.0 -50.0 50.0 -50.0

media 1 1 1 -2

media 0 1 2

media 2 1 3

media 0 1 99 -1 -2 -3

boundary 99

end geometry

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

' Definitions Block

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

read definitions

location 1

position 110 0 0

end location

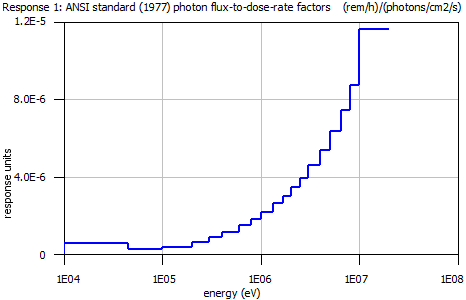

response 5

title="ANSI standard (1977) neutron flux-to-dose-rate factors"

specialDose=9029

end response

distribution 1

title="Cf-252 neutrons, Watt spectrum a=1.025 MeV and b=2.926/MeV"

special="wattSpectrum"

parameters 1.025 2.926 end

end distribution

gridGeometry 7

title="large meshes in paraffin, 5 cm mesh for shield thicknesses"

xLinear 5 -25 25

xLinear 12 30 90

xplanes 100 110 120 -30 end

yplanes -50 -40 40 50 end

yLinear 7 -35 35

zplanes -50 -40 40 50 end

zLinear 7 -35 35

end gridGeometry

end definitions

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

' Sources Block

' Cf-252 neutrons, Watt fission spectrum model

' with a=1.025 MeV and b=2.926/MeV

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

read sources

src 1

title="Cf-252 neutrons, Watt fission spectrum model"

strength=4.05E+07

cuboid 0.01 0.01 0 0 0 0

neutrons

eDistributionID=1

end src

end sources

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

' Tallies Block

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

read tallies

pointDetector 1

title="center of detector"

locationID=1

responseID=5

end pointDetector

meshTally 1

title="example mesh tally"

gridGeometryID=7

responseID=5

noGroupFluxes

end meshTally

end tallies

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

' Parameters Block

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

read parameters

randomSeed=00003ecd7b4e3e8b

library="v7-200n47g"

perBatch=10000 batches=10

fissionMult=0 noPhotons

end parameters

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

' Importance Map Block

'-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

read importanceMap

adjointSource 1

locationID=1

responseID=5

end adjointSource

gridGeometryID=7

macromaterial

mmTolerance=0.01

end macromaterial

end importanceMap

end data

end

4.1.5.1.2. Output

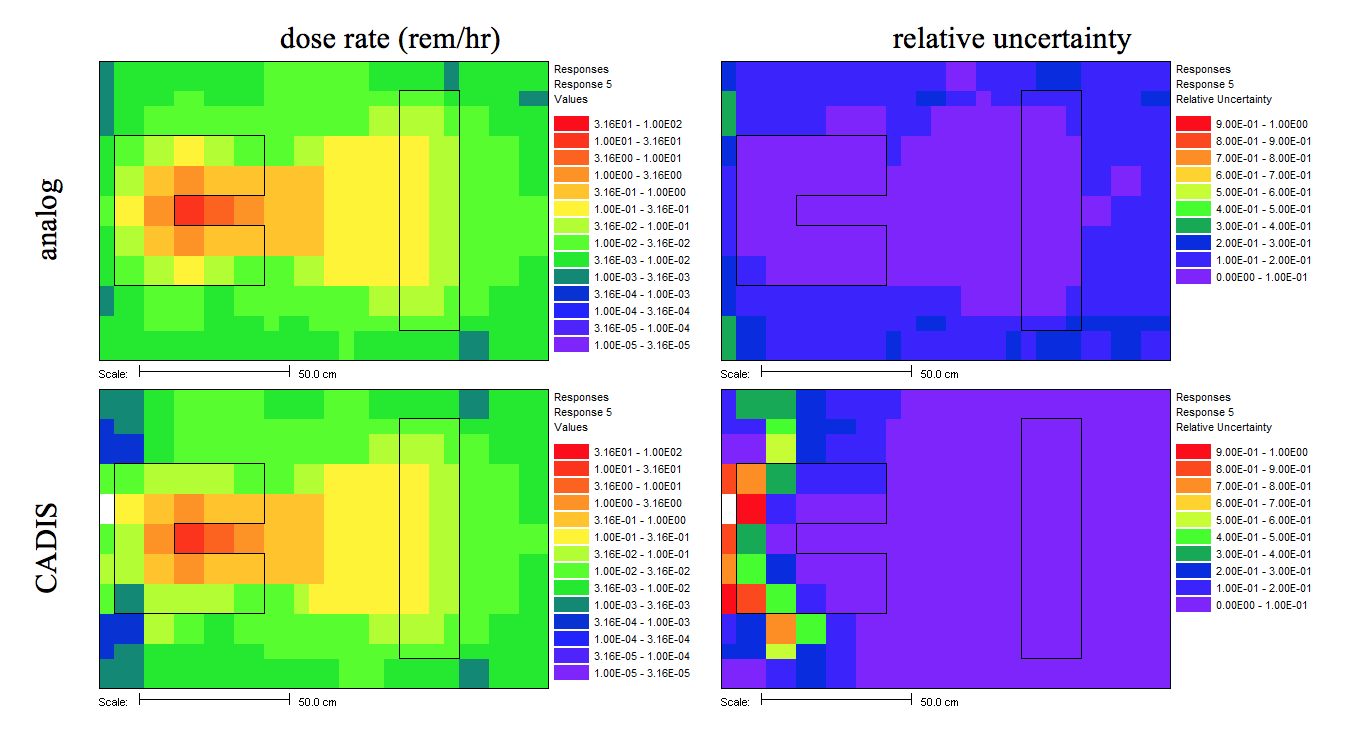

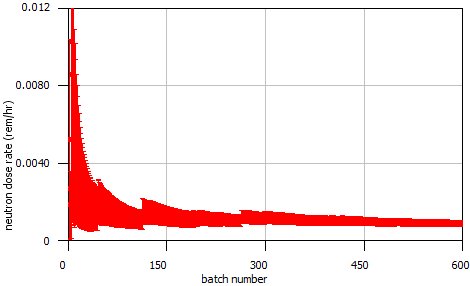

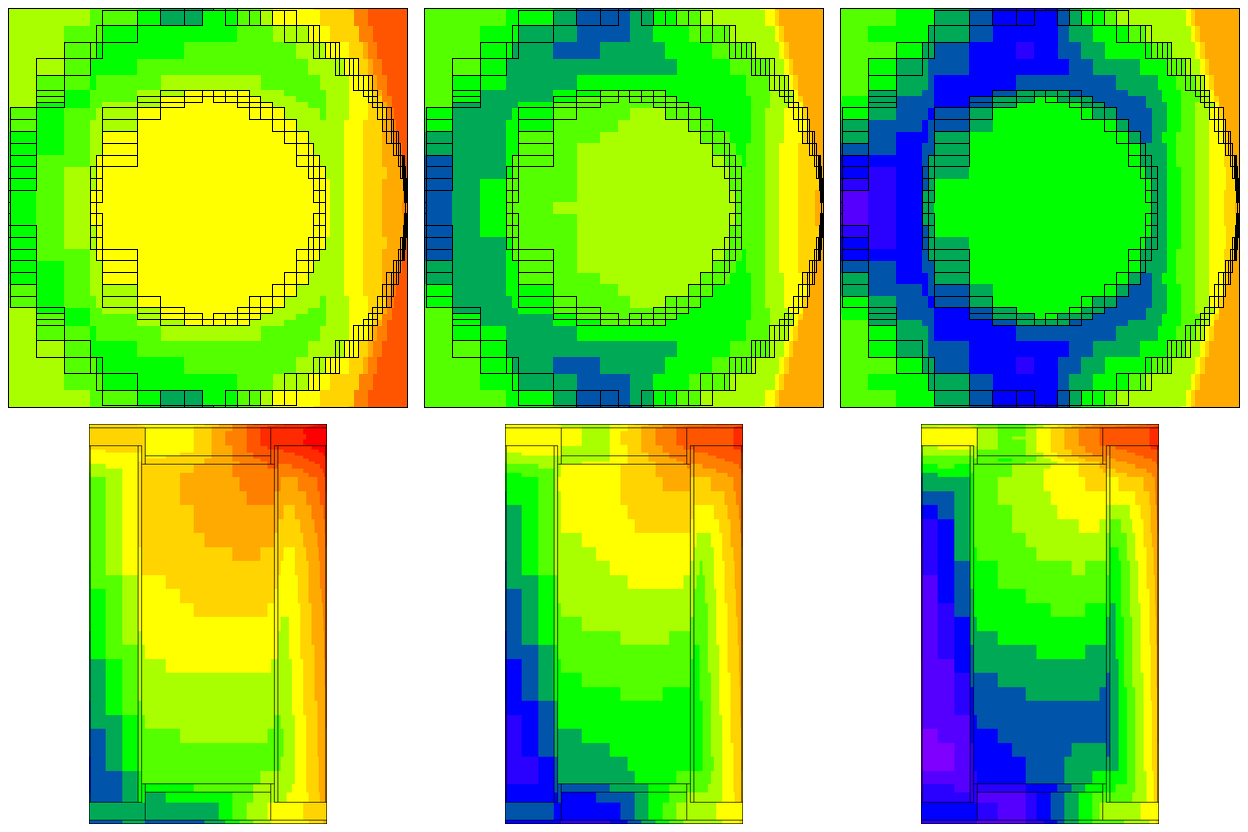

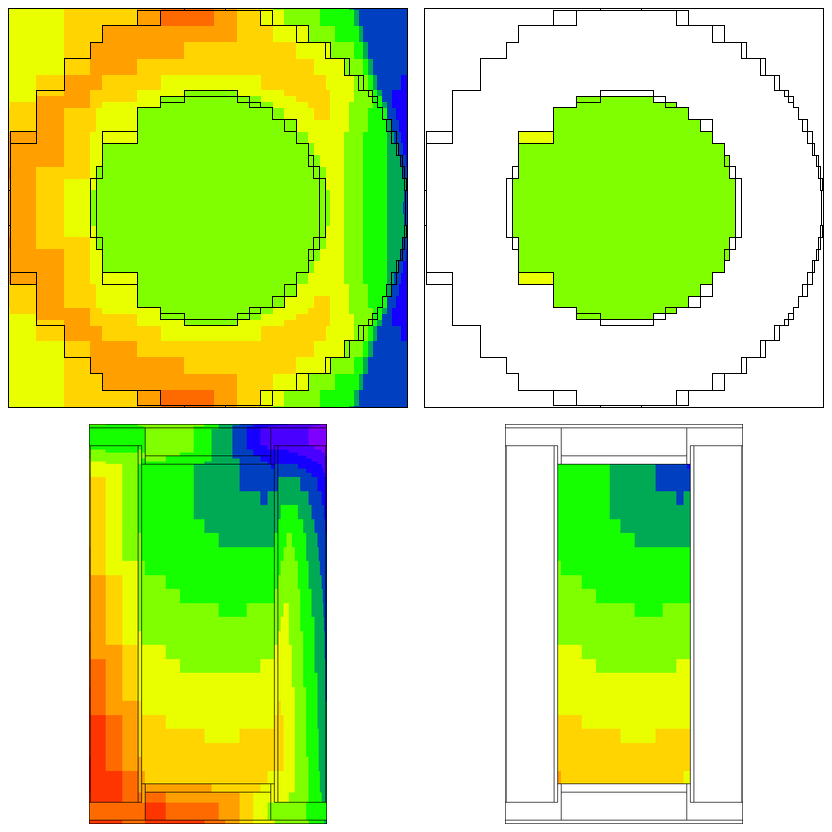

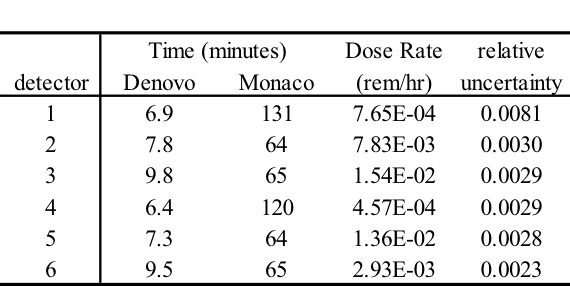

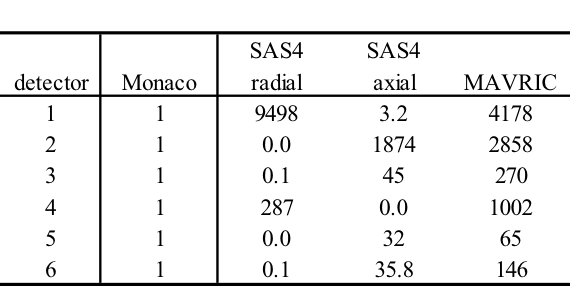

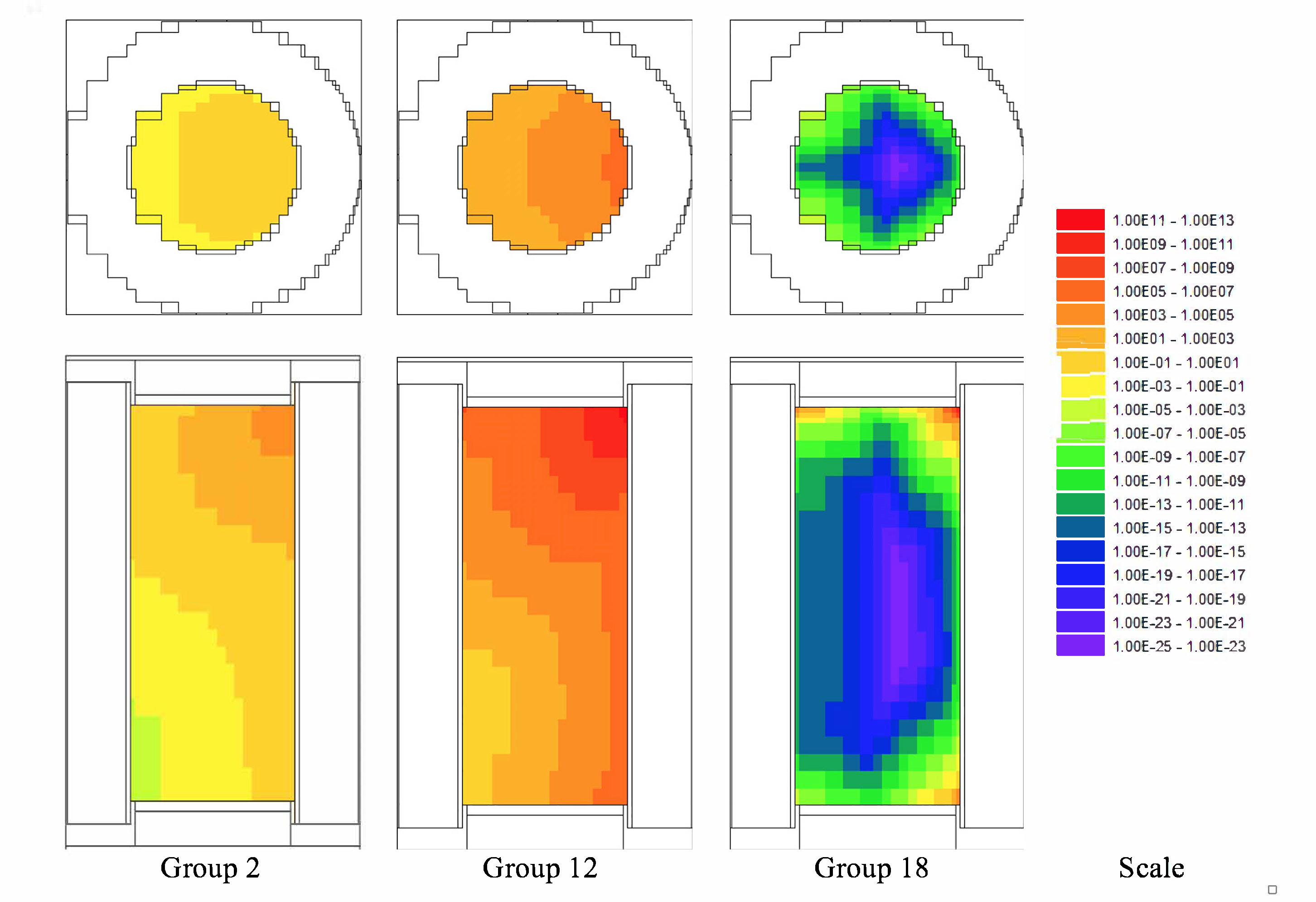

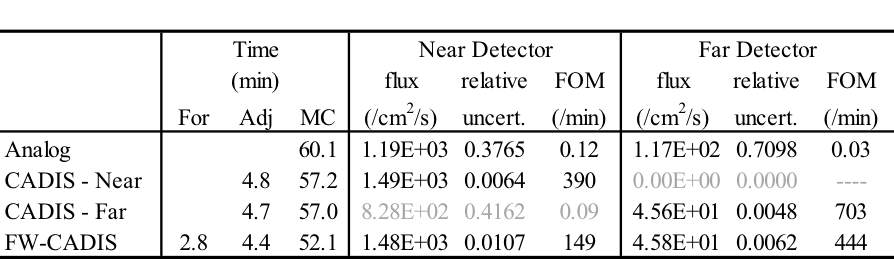

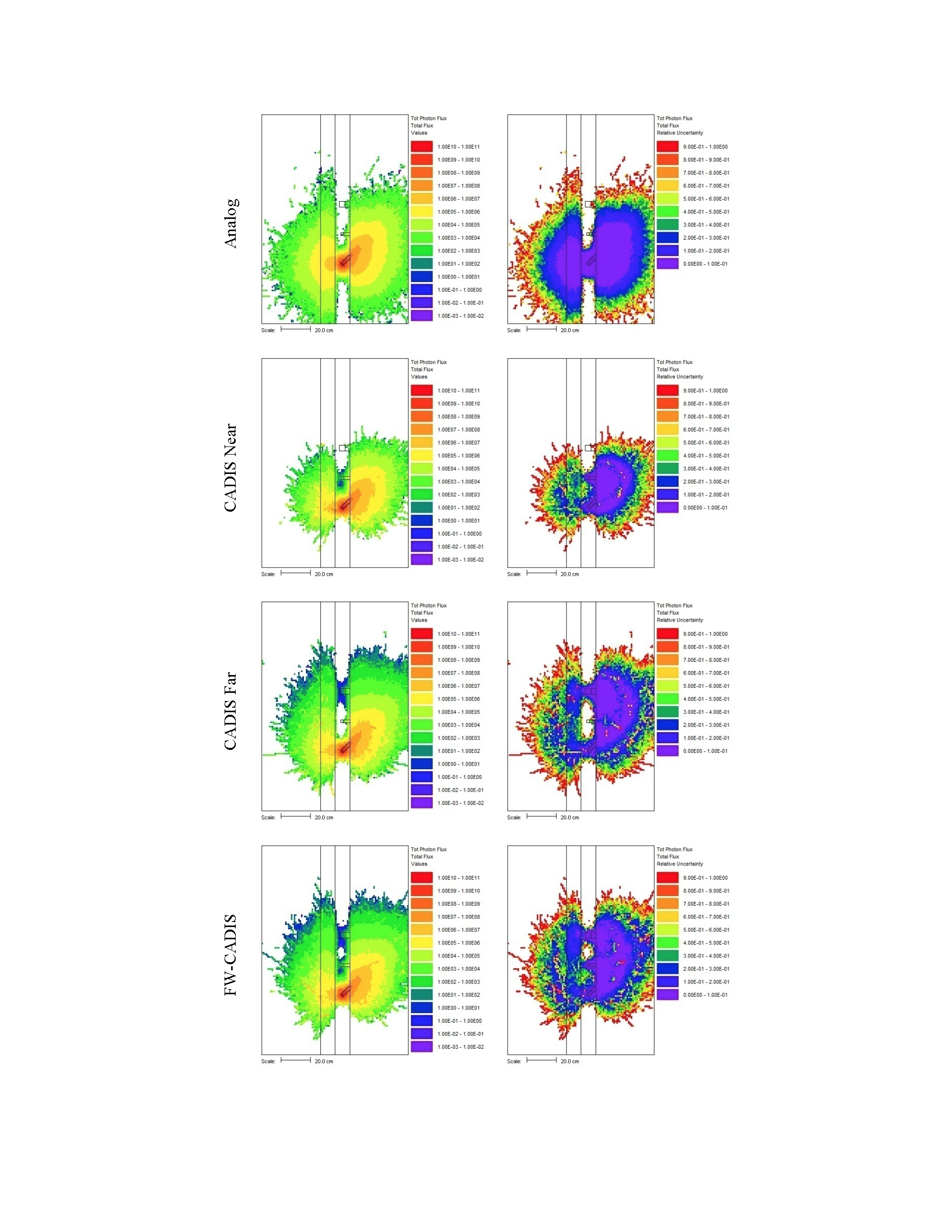

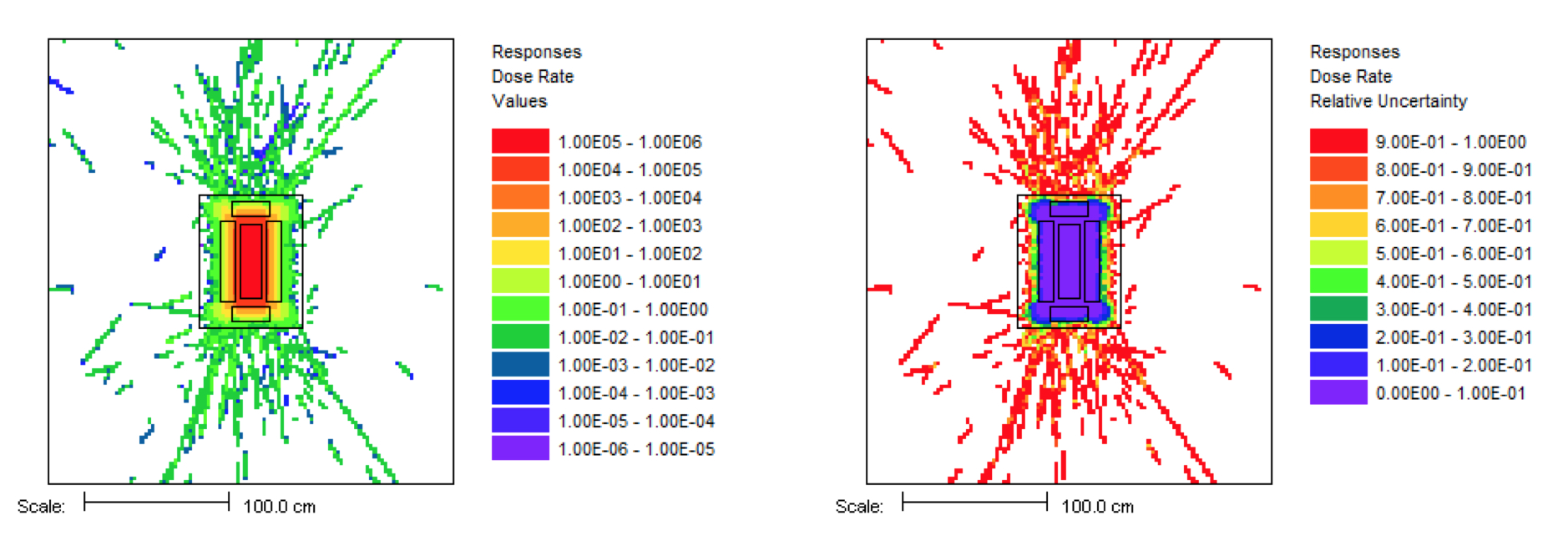

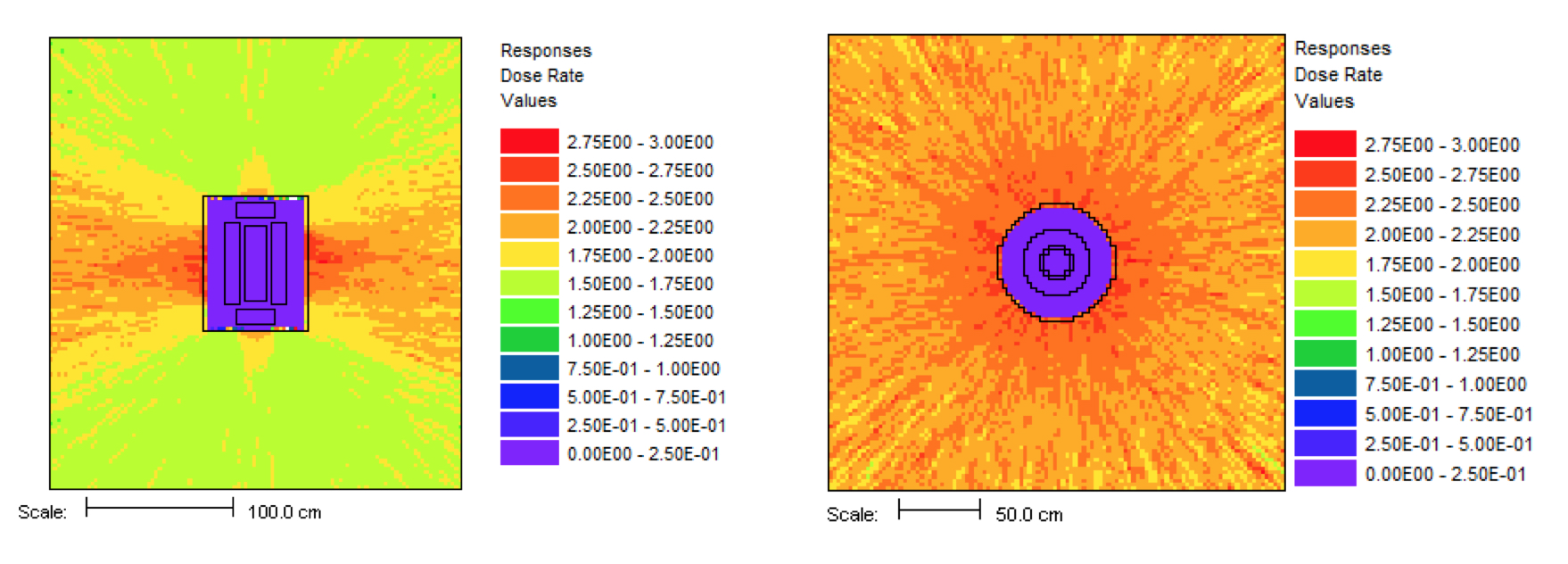

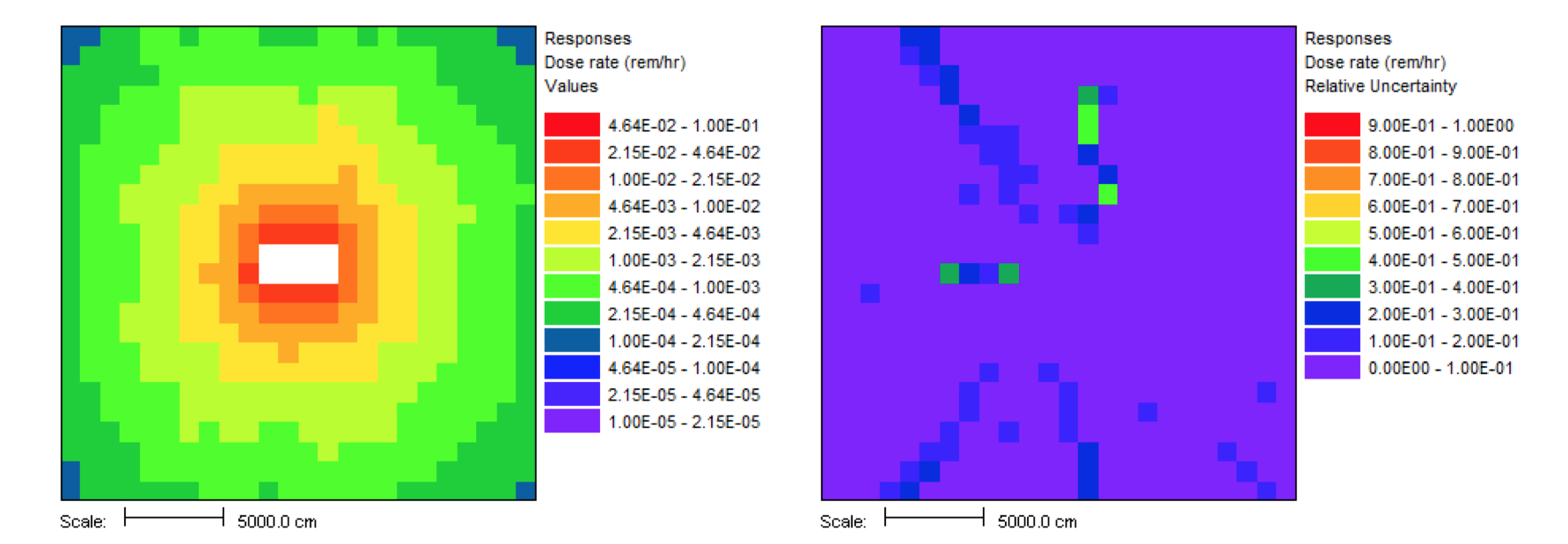

MAVRIC results for the point detector response for the 20 cm case are shown below and in Fig. 4.1.6.

Neutron Point Detector 1. center of detector

average standard relat FOM stat checks

tally/quantity value deviation uncert (/min) 1 2 3 4 5 6

------------------ ----------- ----------- ------- -------- -----------

uncollided flux 1.06384E+01 1.88744E-02 0.00177

total flux 2.36367E+02 5.47276E+00 0.02315 8.10E+02 X - X - X -

response 5 1.28632E-02 1.74351E-04 0.01355 2.36E+03 X X X X X X

------------------ ----------- ----------- ------- -------- -----------

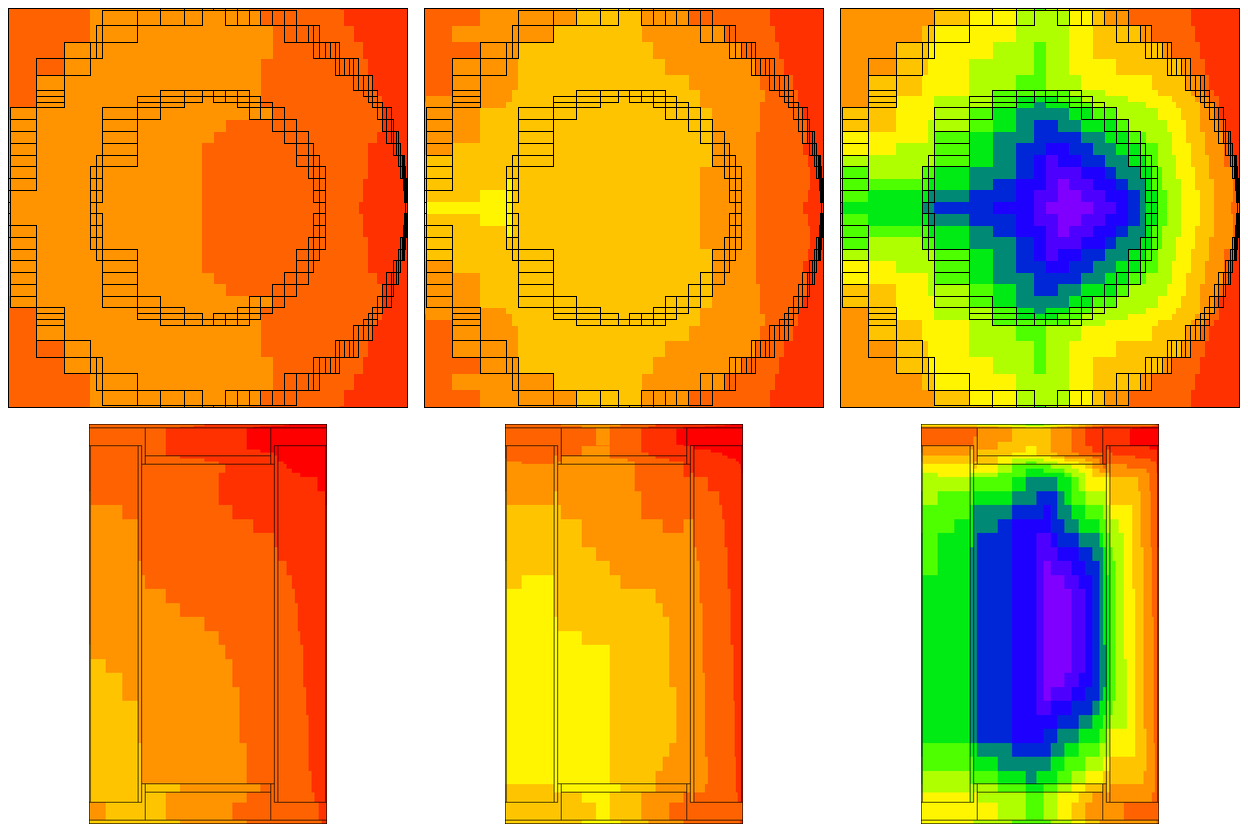

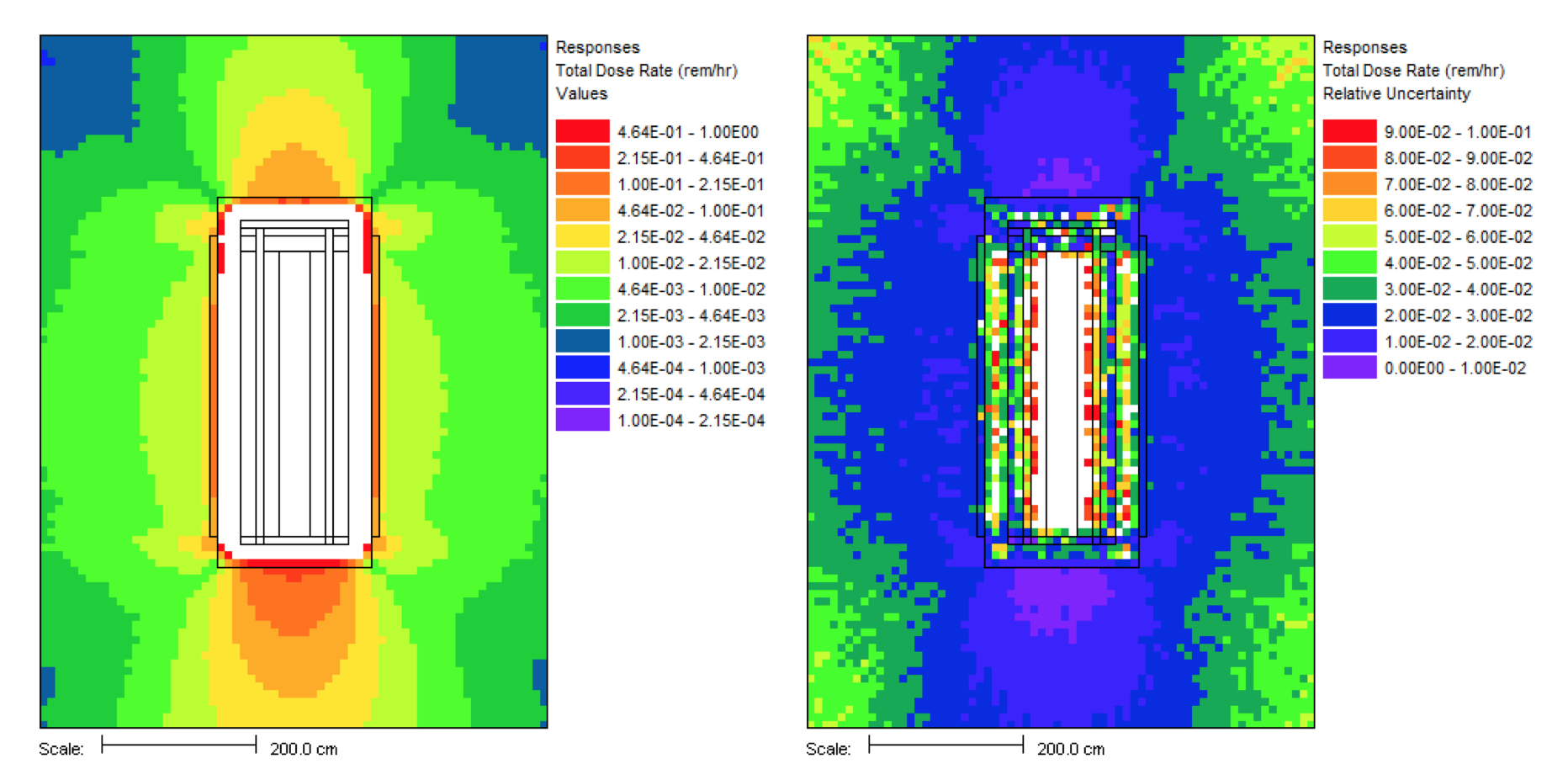

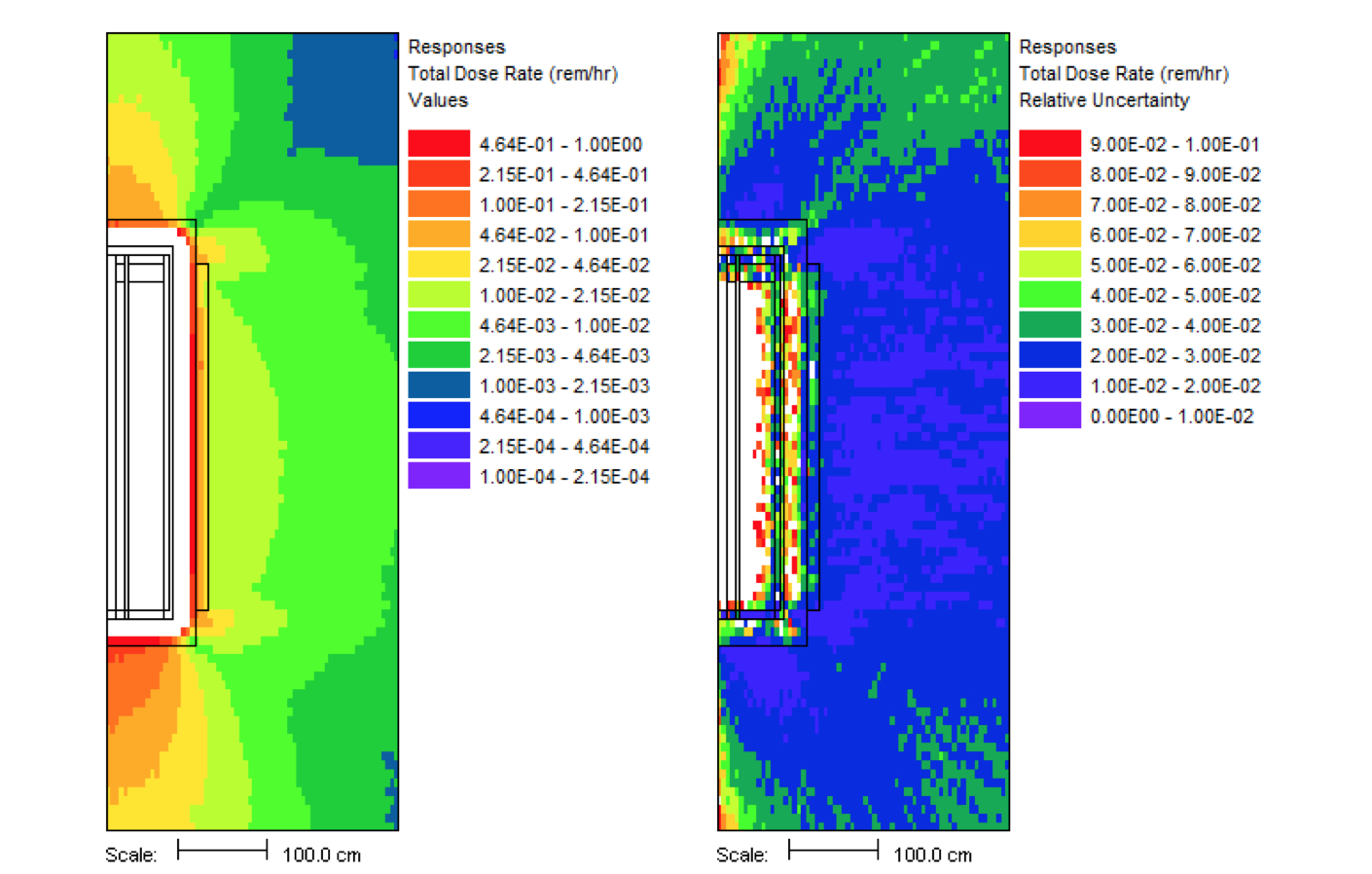

This problem took only ~2.5 minutes (0.2 in Denovo and 2.3 minutes in Monaco) on the same processor as the 20 minute analog case. (The figure of merit [FOM] is 15 times higher than the analog.) Note that the point detector dose rate is the same as the Monaco analog sample problem, but the relative uncertainty is smaller with less computation time. CADIS has optimized the calculation by focusing on neutrons that contribute to the dose rate at the detector location at the expense of neutrons in the paraffin block. This is demonstrated by the mesh tally of dose rates where the values for the dose rate are lower in the paraffin block and the relative uncertainties are higher. Since the calculation was optimized for the position of the detector, dose rates in other parts of the problem are underestimated and should not be believed.

The mesh tally shows that the CADIS calculation did not follow as many particles deep into the paraffin block, so the uncertainties are greater there, but that is what this problem was supposed to do-reduce the uncertainty at the point detector at the expense of the other portions of the problem.

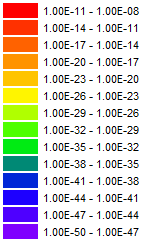

Fig. 4.1.6 Mesh tally showing neutron dose rate (rem/hr) and uncertainties for the analog case and the CADIS case.

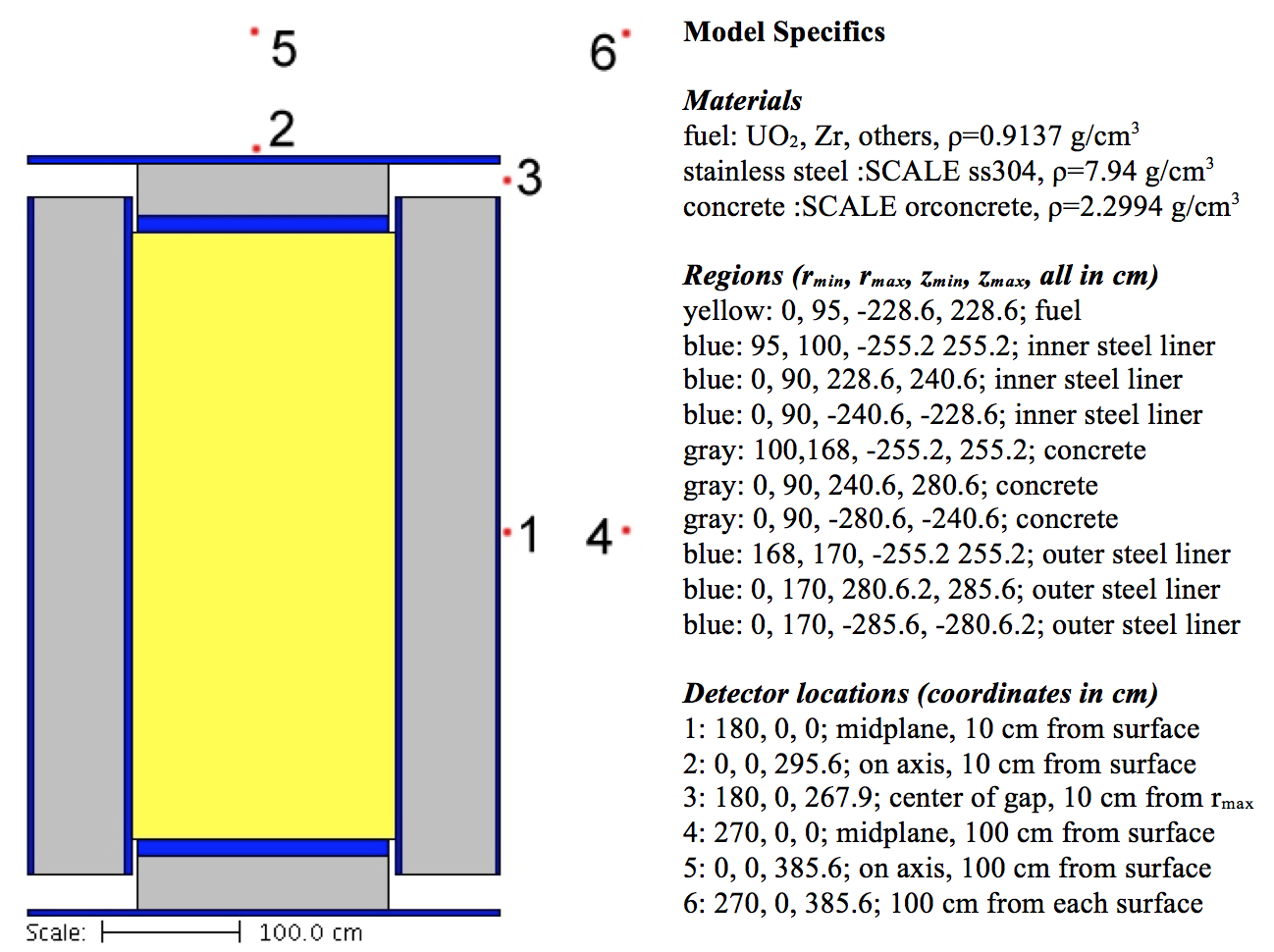

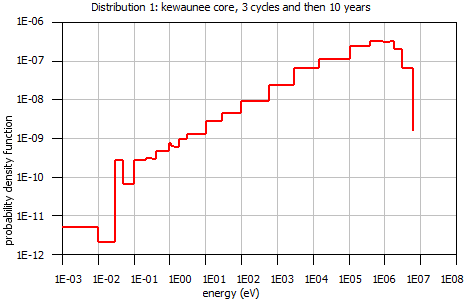

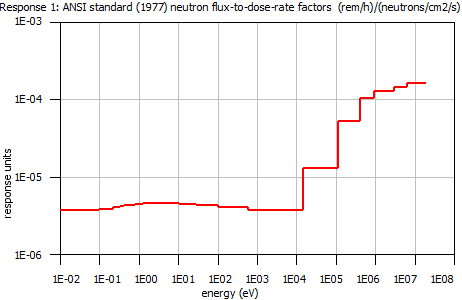

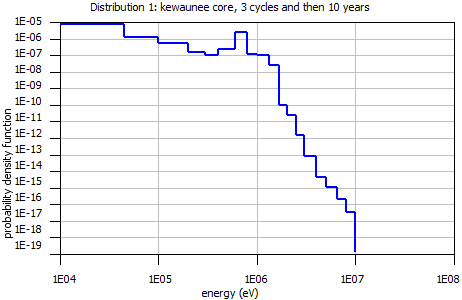

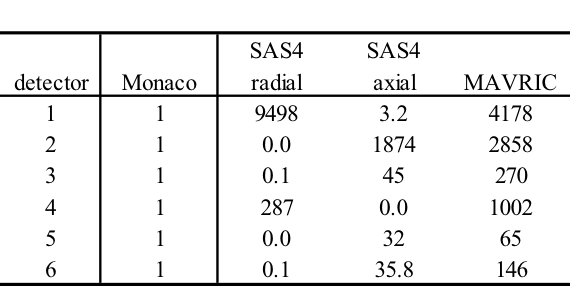

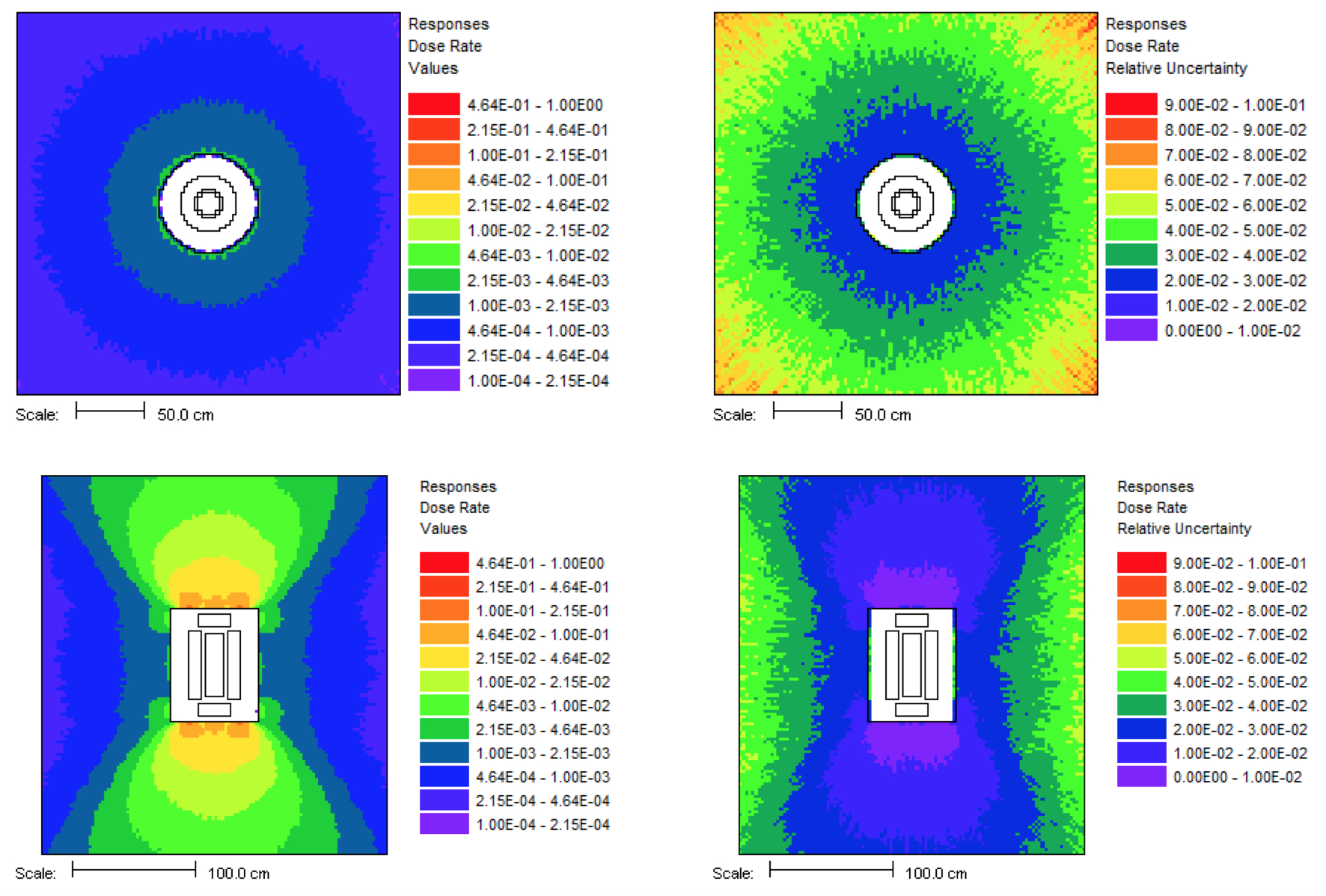

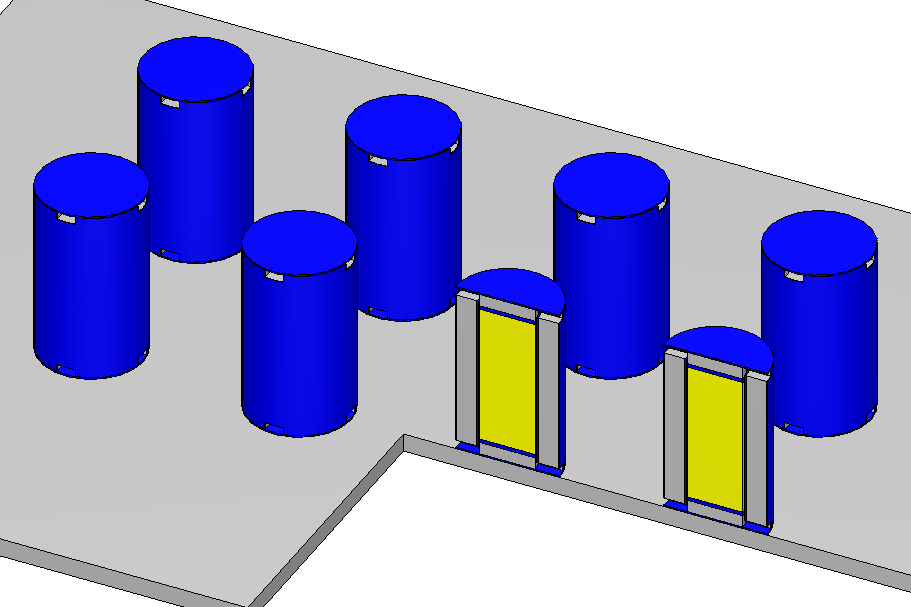

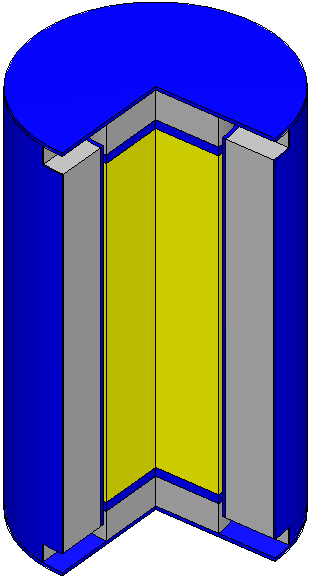

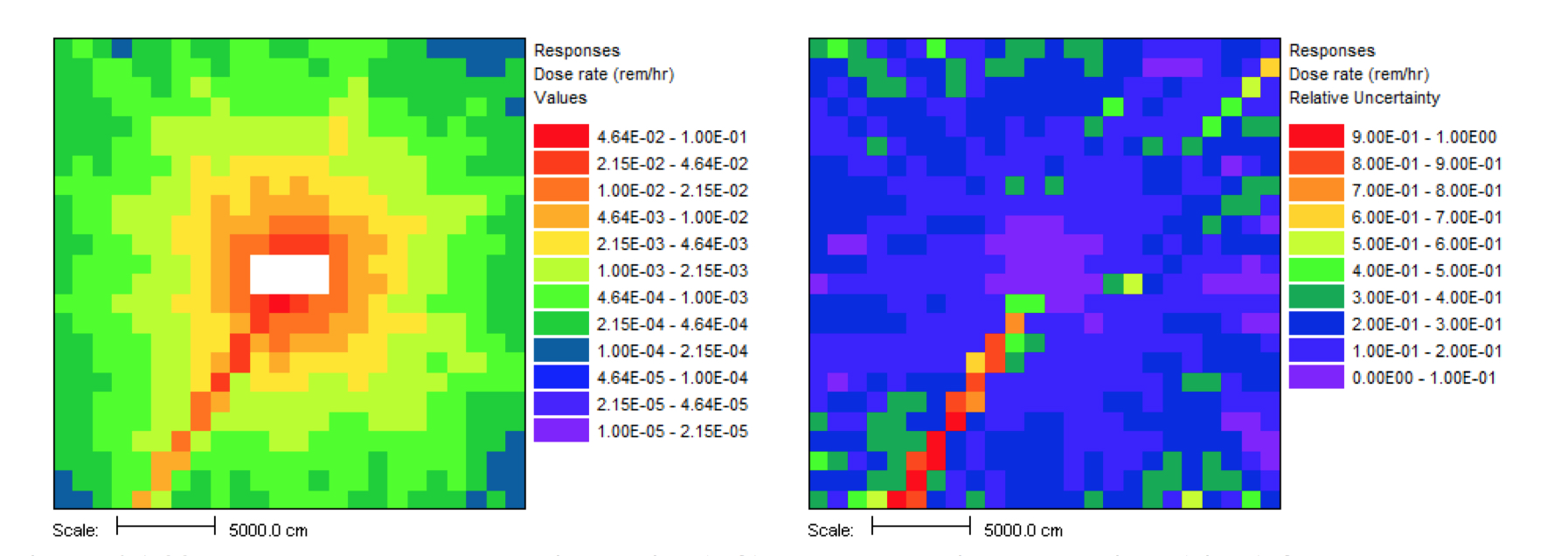

4.1.5.2. Dose rates outside of a simple cask